What’s the use of me? Besides to sing of him whose bread I eat?

Men obsess over use. I don’t mean this as a statement about masculine essence, nor some kind of deep insight into the male Id. It’s just a loose generalization that comes from a lifetime of entertaining clichés. Even while writing this, I doubted the usefulness of that statement; beyond buying me the right to keep on writing a few more sentences. Yet the compulsion to use hangs like Lenin’s portrait over the many committee meetings of our mind. Things are useful or not useful, depending on how many useful features they have— even better if there’s a nice chart comparing useful features. Utility functions allow economists to make normative claims about human behavior based on consumption patterns. Modern philosophy was revitalized by limiting its questioning to that which is useful, ablating the metaphysical junk that did little for mathematics and science. We judge people based on their use, others and ourselves. One kind of con-artist compels us to see women based purely on the utility they provide us. The other kind wants to convince you that art can have its own utility too, represented by tokens traded between young individuals making rational choices. Some obsess over their CVs, a promise of utility; others obsess over net-worth, freed from the anxiety of self-ignorance by a dollar figure. When a family member asks you what you do, what you study, you feel yourself shrink in fear: “so, how much do you make?”

I often have fantasies of use. I think of being stopped in the street, by a woman or child suffering a malady, begging for help. I heroically solve their predicament and ask for nothing in return. Cameras ask me how I did it; I put together the knowledge I’ve attained so far in my short life, and brewed it in the little percolator of intuition. I tells them: I was, for a short instance, sharp like a knife’s edge thrust into an enemy’s lung. I am disposable, but not useless. I’m a twig, thrown into fire to make greater its destructive heat. I’m not useless. Sometimes I have another heroic fantasy. We’re on a life raft, filled with women and children. We are too heavy and despair befalls us all. All I’ve done my whole life is consume, at the cost of others, my own banal urges and desires. I say “well, ‘till we meet again;” I hold my nose and fall backwards into the blackness. The last thing I see are the women and children, confirming my utility with their relief.

Our culture is obsessed with pornography, and I think it’s probably related to the obsession with use. To use and be used. Something useful must have worth, after all. “Our culture?” Well, we’re all part of the same culture now. Welcome. I hear young German kids repeating slang they hear from someone who heard it from someone who said it on Drag Race. I hear slightly older German adults shame them for appropriation, all the while obsessed with being ‘cool’ and listening to whatever post-Afrikan music Spotify deems in current vogue. I resist my chance at epistemic elitism, tho’ we petty-boug usually savor such opportunities: “my appropriation is more raw, semiotic marrow cut from the bone.” Our culture is like modern online pornography, über-focused on the utility of its fucking and unconcerned with frivolous things like plot and tasteful furnishings. YouTube now offers ‘most replayed’ heatmaps, so you can instantly scrub to the money-shot of what you’re watching. Overwrought metaphor? That doesn’t mean it’s not true.

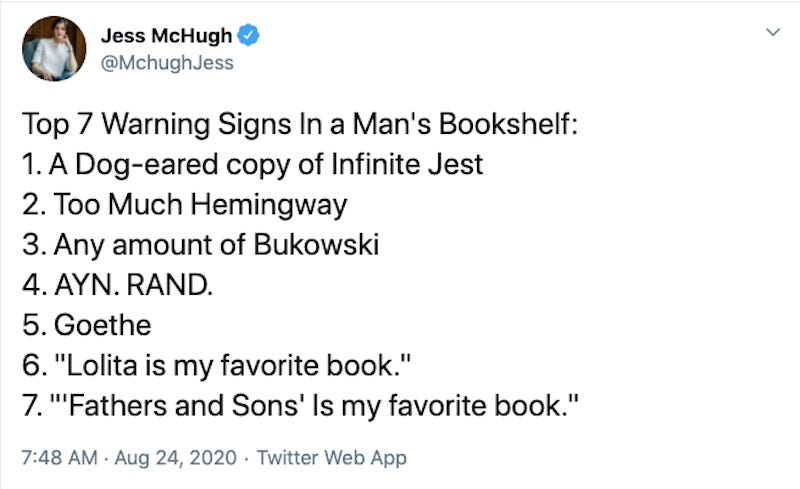

There’s always something a little bit stupid about writing on literature. You can come across as a hot little ignoramus, standing atop a pile of rocks and proclaiming them the shoulders of giants. You can dress yourself up in secondhand suits and say you’re a defender of the great Western canon, standing behind the gates of an elite institution and screaming “I’m one of you” at a closed window. You could half-ironically call yourself a cutting-edge fleshmongering, prostituted-perverted, smut peddler and hope your audience doesn’t know erotica’s been paying bills since at the latest the Victorian ages. In the ever-blurrier world of sci-fy, fanta-sy, Y-A-y, you could even muster enthusiasm by proclaiming your chaste elf-girl-meets-orc-girl fantasia to be ‘just what the doctor ordered’ for those social ills— niche markets mean you won’t face stiff competition from those long-dead authors who rudely refuse to give up their seat at the table.

Simply put, in the now we’re not offered much help by concrete definitions and neat categories. We’re floating in a sea of e-books, which don’t seem to cohere into much more than a vague feeling of isolation and undue cognitive demand. There’s every kind of book out there, and since no-one’s really buying them you’re free to dabble with whatever you want. Genre conventions don’t mean much in an age where flouting convention is demanded of us, and books follow consumer ‘preferences and tastes’ as understood by increasingly sophisticated tools. With the ancien régime institutions long gone, the difference between high-brow and low-brow is a matter of taste; and of course as the marketing expert will tell you, tastes reveal everything.

So what of literature? To even ask the question of what the word means, we become like the hot little ignoramus I invented earlier. Unfortunately for us self-styled rebels, the writers of the 20th-century got all the fun of deconstructing literature and stripping it of its clothes to reveal it was a shallow get-up all along. Reading Twitter (as one must if she aspires to intellectual heights), you’re infuriated by the lack of curiosity and rigor every talking-head shows when he digs up old rotting discourse and adds nothing to justify the space he now occupies in your mind. “Literature is exclusionary!” So is the local soccer club. “It’s elitist to separate high-brow from low-brow!” I don’t see Elon Musk or Joe Biden doing much opera patronage. “Literature is boring and no-one cares!” That’s probably been popular opinion for most of literary history. “The existence of literature makes me feel shame!” Post hoc fallacy; existence itself burdens us with shame.

Am I defending the Western canon? Sure, with a caveat. Like all wars with vague objectives, we’ve been perpetually defending the Western canon since at least the days of the Western Roman Empire, when a lack of Greek knowledge and the decay of papyrus threatened the loss of all those ancient works we’ve now enshrined as the Western canon. If it wasn’t for the literal scraping of palimpsests and the Islamic commandment to accumulate knowledge, our ‘Great Conversation’ would have been even more lopsided towards the obsessions of that abominable sub-continent now Christened “Europe.” Forget the canon for a ‘sec and savor the sad irony: losing our connection to ancient Greek works would mean the loss of our oldest and richest global collaboration.

But what about literature now? A terrible thing about literature is that it makes you wanna write more of it. The secret to the Western canon is that before it was forced by educational administrators onto American students in the 20th-century, it had always been formed by writers engaging with their past so that writers of the future could follow along. It was the first message board, granting sensitive girls & boys an insight into the passions, dramas, failures of those Great Posters. It was never merely a set of norms, an aesthetic you adopt to min-max your pussy acquisition, a tool for battling the Supreme Court, or something with which you bludgeon your enemy. Writers born before the social media age, being a sensitive bunch isolated from the world they’d spent hours describing, had only their foremothers-fathers to keep them company through the long loneliness of solitary labor.

You see, most writers die and do so uneventfully; garnering more fame for their bad temperaments, sexual indulgences, and failed ambitions than even a written single sentence. Canons, in the West and elsewhere, had always sentimental roots that comforted the thousands of unsung, unread writers now long since dead: “write something good enough, and maybe the pain you’ve caused yourself and others would have been worth it.” Most of us mediocrities can only hope that further down the line, someone sensitive to our pathetic plight might think of us as a dying flame needing to be kept burning; Mozart’s first biographies lamented that such a talented child should die so poor and forgotten.

So there you go. There’s maybe some use for you, after all.

Was reminded of a recurring ending I keep. Walking up to the bathroom mirror, hands on the vanity, laughing, then walking out and shutting the door.