The Problem of Scale in Anarchism

An introduction to Aurora Apolito's seminal work of "economic science fiction."

In this Substack post, we’ll be doing some exegesis, explanation, and elaboration of “The Problem of Scale in Anarchism and the Case for Cybernetic Communism” by Aurora Apolito (2020).

The problem of economics is essentially a subset of the problem of social organization. We receive the term “economics,” or οἰκονομικά, from Aristotle’s theory of social organization which located the rhizome of Classical Greek social organization in the οἶκος, or “household.” Aristotle had sound reasons to support this theory — Classical Greek economy was dominated by private family-operated craftsmanship, trade between individuals that generated indirect taxes for the state, and slavery or other cheap labor1. When the population grew beyond capacity, the ancient Greeks would colonize and found new households away from the mother polis which created new trade routes and thus more revenue for the state — new colonization efforts were indeed led by οἰκιστής. Unfortunately for the Greeks, the larger the size of the ‘ancient Greek world,’ the harder it became to maintain the social organization which made stability and trade possible. Indeed, under the political and economic innovations of the Romans, the ancient Greeks enjoyed a newfound level of stability and wealth. We therefore understand scale to be a significant problem of social organization, such that an economic system which results in growth will inevitably present challenges in how to maintain the social organization under which said economic system allows for growth.

“The problem of scale is perhaps the most fundamental problem of anarchism.”

Apolito qualifies her concerns first by stating: “we all know by direct experience that anarchism works well on a local scale.” What she means is that humans are quite good at what we might call ‘spontaneous’ social organization. Anarchist initiatives such as “Food-Not-Bombs, infoshops, small publishing houses, anarchist bookfairs, mutual aid initiatives, Antifa, worker-owned cooperatives, street medics, hacker and maker spaces, …” succeed locally because they do not present the potential for a level of growth which presents a threat to said spontaneous social organization. This is what Apolito refers to as “the small scale;” in the case of anarchism, it works on “the small scale” because spontaneous social organization is sufficient.

What about beyond “the small scale?” Here, Apolito introduces the “main criticism” levelled against anarchism — anarchism lacks “a convincing theory of how a decentralized, non-hierarchical form of organization can be scaled up to work efficiently on ‘the large scale.’” Apolito mentions an anecdote from Trotsky’s autobiography2 who laments that “his anarchist comrades were unable to provide a good plan for how to run the railway system.”

Is this a truly serious problem for anarchism? Yes but not exclusively so. In fact, there’s never a guarantee for any system to ‘work’ at a large scale, whether we speak of physical systems or political systems. “Too big to fail” was a prominent catch-phrase during the global financial crisis of 2008, where strong political and financial action was necessary to deal with the economic crisis caused by poor financial policies and predatory lending. In addition, the economic system of a polis might work at a larger scale yet nevertheless be unsustainable due to political or social problems.

Apolito discusses that side of the anarchist movement which advocates for the political primacy of the “local” and which dismisses the scale problem entirely such that all social organization should be done on the level of what we might call “small communities.” Apolito finds this undesirable because it conflicts with what we might call the large scale belief in the liberation of all of humanity. Indeed, it is only because of capitalism’s development into a system of global scale that we are capable of sustaining our current population — the loss of that system without a replacement of equal scale will surely result in loss of life. Apolito also rejects market mechanisms including socialist market mechanisms as she argues they optimize towards cost/energy minima in order to maximize profit at the cost of all that is immaterial to generating profit3.

If we reject market mechanisms, then what precisely are we ‘scaling’ such that we move beyond the “local?” Apolito refers to the “large scale distribution of services,” with services being generally the distribution of all that fulfills the needs of a polis including transportation, healthcare, food, materials, etc. Why are “local” communities incapable of providing these? Because they require a sophisticated level of coordination of labor and a joint understanding of mutual benefit, and furthermore are resource-costly by virtue of being services — “local” communities wish to restrain growth precisely to remain “local,” and therefore are incapable of the sort of growth which allows for “large scale distribution of services.”

Capitalism provides “large scale distribution of services” by virtue of the profit motive. Labor is coordinated within a firm in order to produce a profit at the benefit of both worker and firm. For private goods traded in markets, this seems sufficient as firms can generate profit from investment, production, and the distribution of commodities. However for services enjoyed by the commons, it is clear that firms will underprovide as there are no market incentives to provide the service yet clear non-market incentives. A classical example would be national defense. There is no market incentive to provide national defense to the commons as it is generally enjoyed as a right endowed upon the commons. However, there are clear non-market incentives as most firms have stability and security in their vested interests.

Apolito argues that for this reason, capitalism is poor in providing services as it incentivizes minimal cost above all things else and thereby discourages the provision of services that are higher in utility for all compared to the utility produced by a firm’s profit at the point of sale — this is a classical collective action problem. For example, car-based transportation is “inefficient and environmentally disastrous,” the supply of knowledge is kept artificially scarce through academic publishing, healthcare (at least in the US) is inefficient and unevenly distributed, and the economy revolves around the quick, disposable consumption of cheap products4.

What are the alternatives? One alternative would be relying on the state to provide services as the state doesn’t rely on the price signals of markets in order to allocate capital and resources. Today, practically speaking, all states function as a mixed economy in which the state provides services, regulation, and undertakes actions to influence the macroeconomic conditions under which commodities are traded by both private and public-owned firms. However, this ‘post-war consensus’ has been eroded ever since the rise of neoliberal economics in which price stability and the free flow of capital and labor without the inefficiencies of the state are taken as political goods5. As a consequence, the ‘post-war consensus’ is increasingly seen as both politically and economically unfeasible.

Another alternative would be to do away with markets all together and endow the state with the necessary power to distribute goods and services instead. Taking into consideration the sophisticated means of production necessary for most goods and services, and the scale at which most modern states exists today, it stands to reason that a severe level of social organization and control is necessary to accomplish what one might call a functioning economy. The consequence of said severity is what we see often in economies which cannot function without a large state: the parts of the state which excel at social organization and control balloon in size and become the chief drivers of the economy while the rest languishes due to a lack of incentive.

Militaries in general thrive under these conditions because militaries tend to have rigid levels of social organization, and the ensuing militarization of society allows for a large degree of control. Military and medical technologies will advance because they directly benefit the state while others aspects of society will be neglected or even suppressed. An example of such a society is modern Russia, a modern mixed economy. Stagnant economic growth was exacerbated by dwindling oil and petroleum income as well as global sanctions in the wake of conflicts with Georgia, Syria, and Ukraine. Naturally, this caused the Russian state to invest heavily into the military — in 2025, military spending will account for 40% of the federal budget which goes directly to arms production and military salaries. In addition, another 10% of the federal budget goes to internal security and police. Consequently, modern Russia is becoming increasingly rigid and hierarchical in contrast to the anarchy and instability of Russia after the Soviet Union.

Therefore, it is not sufficient to merely grow the state and centralize power; when an economy succumbs to inefficiencies or poor planning, the use of violence and authority inevitably follows — violence is indeed the oldest and most base form of authority. The connection between violent authority and economics was already remarked upon in the first work of economics (Οἰκονομικά) ascribed to Aristotle, in which forced labor is described as the foremost and most essential private property6. Considering that anarchists and communists wish to do away with violent authority and private property respectively, it’s clear that our proposed alternative to markets needs to be sophisticated enough such that forced labor is not necessary.

“[S]caling a model of organization and production based on anarcho-communist principles is possible only in the presence of enough capacity for informational complexity.”

Apolito moves on to discuss two communist alternatives to the market system which relied on computational methods, namely ‘linear programming’ and ‘cybernetic communism.’ I’ll explain these methods, and expound on what they contribute to the problem of scale.

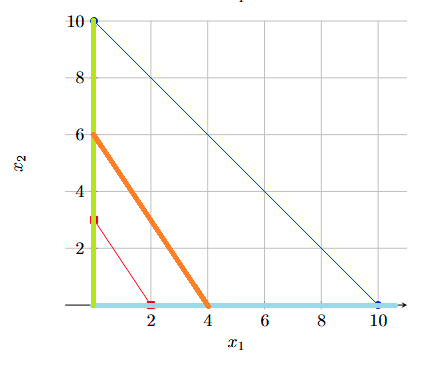

What is ‘linear programming?’ The idea is simple: to solve a problem, find the optimal values of variables given certain constraints. Kantorovich found that if we can describe the problem in terms of a shape, we can find the optimal value of variables by finding the very edge (corner point) of the shape furthest towards what you want to maximize. With this method, we can solve linear problems (in which two things always remain in a constant proportion) by merely solving for the corner point rather than trying to check every combination. Let’s give a classical example, using Kantorovich’s ‘valuations’:

Let’s say a firm has a piece of land of size L, planted with either corn or wheat. The firm has F kilograms of fertilizer, and P kilograms of pesticide. Every hectare of corn requires F1 kilograms of fertilizer and P1 kilograms of pesticide, and every hectare of wheat requires F2 kilograms of fertilizer and P2 kilograms of pesticide. Let’s take V1 to be some valuation of corn, and V2 to be some valuation of wheat per hectare. Let x1 be the area of land planted with corn, and x2 the area of land planted with wheat. Given the valuations (V1 and V2) you give to corn and wheat, you can maximize your total value by choosing the optimal choices for x1 and x2.

Now that we have our small economic model, we can solve problems by plugging in the relevant numbers and then maximizing x1 and x2. To start, let’s say we have a land of 10 hectares. We then figure that neither crop can be planted on more than 10 hectares, and that they stand in proportion such that we have 5 hectares of corn if we have 5 hectares of wheat. This is a linear relationship, and we can map that out as such:

That’s our first constraint — whatever the answer is lies behind this blue line. Now let’s say we value corn slightly higher than wheat: let V1 equal 3 rubbles and V2 equal 2 rubbles7. This means that we favor planting corn over wheat, and it determines the direction of the line on which our optimal solution lies. If corn has no value, then at no point will the optimal solution lie anywhere except 0 corn; 0 corn would be optimal. If wheat has no value, then at no point will the optimal solution lie anywhere except 0 wheat; 0 wheat would be optimal. Here is an illustration, where the red line represents V1 = 3, V2 = 2, light blue represents V2 = 0, and green represents V1 = 0:

The orange line represents a line with the same angle as the red line — this will become important later. Next, we set our two other constraints. Let’s say we only have 48 kilograms of fertilizer, and 32 kilograms of pesticide. Every hectare of corn requires 3 kilograms of fertilizer and 4 kilograms of pesticide, and every hectare of wheat requires 6 kilograms of fertilizer and 2 kilograms of pesticide. We then get the following constraints:

Given the amount of fertilizer being 48, the maximum hectares of corn possible is 48/3 = 16 and the maximum hectares of wheat possible is 48/6 = 8. Given the amount of pesticide being 32, the maximum hectares of corn possible is 32/4 = 8 and the maximum hectares of wheat possible is 32/2 = 16. We end up with two addition constraints:

Given our constraints, the area in pink represents the only possible choices of x1 and x2. The blue circles represent the edges (corner points) which are the best optimal choices: these are (4,6), (6,4), (0,8), and (8,0). However, only the edge (6,4) points in the same direction as the normal of the red line — that means it must be the optimal edge given our valuations V1 and V2. To verify that is simple: plug in all the edges in our original equation:

Indeed, 6 hectares of corn and 4 hectares of wheat is optimal given the amount of land, fertilizer, and pesticides at hand. The Soviet economy has been therefore been optimized and is perfectly efficient. Да здравствует мир между народами!

Those of you mathematically-inclined however will realize that the optimal solution depends entirely on the entirely arbitrary valuations chosen for V1 and V2. If we flipped the valuations around, the solution would likewise be reversed. Markets have prices signals which provide valuations, such that what is sold for the most profit is the most optimal given the relevant constraints. Ultimately, in our model economy it’s the arbitrary decision of valuation which determines the final optimal answer. Which numbers for V1 and V2 should we pick? We don’t know — that depends on what is needed in terms of supply in order to meet the demand in the economy. Kantorovich’s linear programming does not solve the question of precisely which resources we should value over others given the state of the economy. Without knowing the correct valuations, we will oversupply some resources and undersupply other resources and thereby create inefficiencies and shortages which will cripple our economy.

How do we solve this problem? Apolito discusses what she calls ‘cybernetic communism,’ or the use of cybernetics methods in order to organize the economy without the use of markets or capitalist economy. But what precisely are ‘cybernetic methods?’ The word ‘cybernetics’ conjures up a buffet of different images as the term proliferated across pop culture but as it was originally defined by Norbert Weiner in Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, cybernetics is the science of self-organization through feedback.

Likewise, cybernetic communism would involve economic actors which use self-organization through feedback in order to control and make decisions about supply. Through the technological means by which this might be achieved is by no means trivial, the core concept is intuitive. For example, self-organization through feedback is how the body maintains homeostasis — when the body temperature drops, the hypothalamus induces physiological responses all throughout the body in order to maintain a stable body temperature. This is not a tyrannical top-down order by the brain, but rather a series of signals triggered by another signal that spreads throughout the body.

Cybernetic communism would work in a similar fashion. Rather than a centralized body, each node in a network would ‘send’ a signal forward to a higher node which would be responsible for providing feedback. This might be best demonstrated by the following model for production:

I’ll first discuss the upward arrows. “Steel Firm A” provides a signal to “Steel” about production: both “Steel Firm A” and “Steel Firm B” can together provide 1 unit of steel to the economy. Based on the information provided by “Steel Firm A” and “Steel Firm B,” and all other steel firms, “Steel” reports to “Industrial goods” that “Steel” can provide 1 unit of steel. “Industrial goods” collates that information along with the information of all other industrial sectors such as “Copper.” That information is passed onto “Production,” which collates that information along with the information it gets from all other sectors of production. This information provides a picture of the ‘state’ of the economy and its capabilities for production.

What I’ve described is a good start for a sketch, but it doesn’t allow for self-organization. Information might flow upwards towards a centralized point, but without feedback there is no mechanism to allow for efficiency in production. If for example a bridge-building firm is missing steel, there is no way for the steel firms to know there’s an increase in demand and respond accordingly. Therefore, each node must also provide backwards negative feedback to each subordinate node. We can expand on our previous example to give a picture of how feedback might work in our model economy:

In this example, we see that the “Production” node provides ‘demand information’ to the “Industrial goods” node: there is demand to produce a bridge. The “Industrial goods” node responds to the feedback by issuing that ‘demand information’ to the “Bridges” node, which responds with the ‘demand information’ that it requires 2 units of steel. Based on the ‘supply information’ given by the “Steel” node, the “Industrial goods” node responds to the ‘demand information’ given by the “Bridges” node by issuing ‘demand information’ to the “Steel” node: we need to increase production and produce 2 units of steel. In response to the ‘demand information,’ ‘supply information’ is provided to the “Production” node: 1 bridge can be produced with 2 units of steel.

Our intention with this system is essentially to solve a question we’d posed earlier in Apolito’s discussion of linear programming: if valuations are arbitrary, which ones do we pick for an efficient economy? In our model economy, the valuations would be made based on the ‘demand’ and ‘supply’ information sent from each of the nodes to their respective superordinate node. These valuations would be traded amongst the connected nodes through some sort of blockchain system 8, in which network consensus is required to change valuations in the record. Analogous to how currency worked in the Soviet system, goods would be ‘paid for’ with some sort of cryptocurrency where all nodes take a role in validating the transfer and securing the transaction record. This means that information can flow ‘upwards’ towards superordinate nodes by decentralized means, with mutual distrust among each node preventing the sort of ‘book-cooking’ or inefficiencies that come with incomplete or wrong information about valuations. If information about valuations is independently verified by each node, it remains both decentralized and trustworthy across scale. It also doesn’t require firms to be controlled by a center authority, as any firm with the means may participate in this cryptocurrency network. This would shift control from a top-down punitive model to a bottom-up decentralized model, in which nodes can self-regulate using feedback9.

Why the emphasis on nodes? Nodes are merely the most straightforward representation of data, which is meant here to be atomic units of some sort of value representing information. Apolito emphasizes information because she argues that alternatives to market economies are possible only with a sufficient “capacity for informational complexity.”

Apolito justifies her claim by drawing from research done with data collected in the Seshat Global History Databank. One paper used a mathematical method for isolating and mapping out specific components in a dataset, and found that historical polities, when mapped onto a two‑dimensional space of scale and information‑processing capacity, initially cluster tightly. This suggests that growth in scale can occur with minimal gains in informational complexity. However, upon reaching a certain “scale threshold,” two categories of polities with distinct trajectories emerge: one category continues to grow in scale without much increase in informational capacity, while the other category begins to expand its information‑processing capabilities. Those polities that surpass a subsequent “information threshold” can then sustain further scale increases, creating a dispersed intermediate region that reflects diverse developmental pathways. Beyond this point, polities converge into a new cluster characterized by broadly high scale societies supported by advanced informational complexity — though that is probably best explained by the dataset’s emphasis on pre-modern societies.

This relates our discussion back to the question of social organization. Polities which grow rapidly in scale without the sort of information complexity which makes self-organization possible (our previous model is merely one example) will tend towards authority and threats of force as a way of maintaining social cohesion and organization. Without authority and threats of force, it simply becomes impossible to maintain a political economy capable of sustaining a polity beyond a certain scale — the organization necessary for the people of the polity to have goods and services just won’t be there. However, authority and threats of force make for an inherently fragile political economy vulnerable to shifts in power. Therefore, Apolito advocates for polities of mass informational complexity capable of dealing with economies at scale.

“[A]narchism is at heart a process of self-organization in complex networks.”

With the background sketched out, we can now move on to address Apolito’s key research question: what is information complexity in a self-organizing network and what role does it play in our model economy? Simply put, greater informational complexity allows for a greater amount of resources to perform a certain task. If a function f is some arbitrary computable function, the information complexity of a function f is the minimum amount of information A and B need to exchange to compute the function f. If we take the view that the problem of distribution of goods and services in an economy is a computational problem which grows in difficulty as polities grow in scale, then we can conclude that there exists at least some sort of minimum complexity necessary to sustain a particular polity without resorting to markets or authority. But what exactly do mean by complexity?

We’ll tackle this problem by first attempting to give a rigorous definition of complexity. Apolito begins by citing Kolmogorov complexity. The Kolmogorov complexity (K) of something is the length of the shortest process (algorithm) that realizes just that something. What makes Kolmogorov complexity an attractive general definition of complexity is its relative flexibility: that something could be anything as long as it is realizable by some process. A rigorous definition is as such:

To put it into plain terms, the K of a process outputting x is just that which we need to accomplish the output x of that process. The definition is open-ended enough to allow for an intuitive notion of complexity. For example, the string ‘ababababababab’ is less complex than the string ‘3194u019jw0wj’ because the former can be realized by the process ‘ab x 7’ while the latter string cannot. Therefore, K(‘ababababababab’) < K(‘3194u019jw0wj’).

However, you might notice the problem immediately. That means that any random string is going to be more complex than anything with any measurable sort of order. That is completely at odds with the goal we’re hoping to accomplish: the notion of complexity we desire is not randomness, but rather a certain structural complexity. In fact, randomness is counterproductive to what we think of as complex social organization. Therefore, while intuitive at first, Kolmogorov complexity does not capture what we think of when we think of complex social organization.

Therefore, we need something different. Apolito introduces Murray Gell-Mann’s notion of effective complexity as a candidate. While ordinary complexity is sensitive to randomness, effective complexity is about describing the information content of the “regularities” in some pattern.

To do so, we first reason that a signal about a random process will always leave us more uncertain than a signal about a non-random process. To see why this is the case, imagine we have two dice. On the first dice A, every side is a 1. On the second dice B, we have the usual exhaustive pairing of 1 to 6 for every side of the dice. If I roll dice A and get a 1, I’ve learned nothing about the process because I know every side on A has a 1; the result is completely unsurprising and I know fully what result I’ll get if I roll again. However, if I roll dice B and get a 6, I’m still completely uncertain about what might come next as every single side on a (fair) dice has an equal chance. This is of course easy to verify using Shannon entropy: a single roll of B gives us 2.58 bits of uncertainty, while a single roll of A gives us 0 bits of uncertainty. It’s intuitive then to see that when something is at its most random and unpredictable, it has the highest uncertainty.

Knowing this, we have a notion of randomness by which to minimize against; the most likely description of x is that which is least surprising, while anything with a high degree of surprise is likely to be random and unpredictable. We can exploit that notion to come up with a definition for effective complexity:

Simply put, we choose the ‘statistical ensembles10’ which have minimal entropy and complexity given some output x, and compute the complexity of the process needed to realize that output. With this definition, we’ve avoided the problem of randomness being definitionally more complex than non-randomness as we reject those statistical ensembles which give unpredictable and random results. By comparing the effective complexity of one process to another given some change of state and picking the most discriminating and parsimonious computation, we have a notion of informational complexity insensitive to random signals.

Okay, but precisely the complexity of what are we trying to maximize? Apolito appeals to the notion of integrated information to make a case for form of “collectivity” which is not reducible down to individual agents. When we maximize the integrated information of a network, we maximize the informational complexity that exists by virtue of the causal dependencies between nodes in a system. To go into detail could be a long textbook on its own, but the notion of how such information complexity may be achieved is analogous to how complexity functions in the brain. For example, visual sight in the mammalian brain functions by visual input from the optic nerve being integrated and distributed by the primary visual cortex to the rest of the brain. This sort of complexity is not reducible down to individual neurons: it is in fact a systems-level phenomenon. The measure of total irreducible complexity in integrated information theory is denoted by Φ. Φ is defined as the summation of all subunits that locally maximize their φ, which is defined as the amount of information intrinsic in a change from one state to another:

Basically, given some subunit of the network and a partition of that network with the smallest amount of information in the system, how more informative at the least is that subunit compared to the partition with the smallest amount of information? In a network where everything functions by virtue of individual nodes, we can expect Φ to be quite small. In contrast, systems in which there is a lot of information complexity by virtue of the causal connections between the nodes, we can expect Φ to be quite high. Given what we’ve learned in our previous section on effective complexity, we can see that our desired constellation for informational complexity is the minimum effective complexity necessary for an integrated information system to output x.

“In a cybernetic communism system art is an instrument for growing complexity.”

So far we’ve worked in abstractions and generalities — but what precisely is the substance of this complexity? What does complexity consist of in a practical sense? Apolito here refers to instruments of connectedness and instruments of complexity. Instruments of connectedness increase the connections and the causal influence between nodes in a network. For example, public transportation increases the connections and causal influence between people physically, while mass communication increases the connections and causal influence between people in a different modality. With higher degrees of connectedness, more is possible: ever more sophisticated forms of production require ever more sophisticated instruments of connectedness in order to efficiently take inputs and distribute outputs.

In contrast, instruments of complexity are what facilitate information between nodes in a network. Apolito gives some examples of science, art, philosophy, music, education, etc. One might also consider less academic examples such as communal sports, dancehalls, worship, parks; generally anywhere one might find social rituals present which serve to increase the level of integrated information between agents. When it comes to instruments of complexity, our examples are far less rigorous due to the generality of these concepts; human flexibility and creativity make for greatly diverse instruments of complexity.

Historically, the state has played a great role in maintaining instruments of complexity due to the role they played in social organization. In ancient Egyptian statecraft, religion and state were heavily entwined such that much of social ritual and governance revolved around the divinity of the monarchy. Imbuing taxation and labor with sacral qualities was a way of encouraging people to act (more) voluntarily towards the ends of the state, while the development of writing as a medium for communication allowed for greater efficiency in taxation and trade. Analogously, the development of written Chinese from a way to record divinations to a written language allowed for the complex bureaucracy of the Qin dynasty which achieved an impressive level of centralization.

In liberal traditions of modern statecraft, civil society is made distinct from the social ritual of religion such that the primary function of the state was to maintain its obligations and protect the rights of its subjects. As a consequence, any ‘intervention’ into market economies by the state comes with the caveat that said intervention violates the rights of individuals to pursue their own self-interest as individual economic actors. This makes the question of maintaining instruments of complexity under market economies complicated: how much intervention, and thereby violation of rights, is justified given the ends?

In the United States, a trend towards privatization and ‘marketization’ since the 1970s has indisputably resulted in the decline of public mass education despite growing costs of education. Mass education essentially being a redistributive policy means that it is unlikely to be profitable as a business, which has forced many universities to become something between a venture capital firm and asset management firm in order to sustain and grow as mass educational institutions open up to the global public. If a modern university wishes to survive, it must put returns on investment over everything else and somehow succeed in making education a tradable commodity— this despite universities being public institutions funded by the state. One of the more fascinating consequences of this ‘marketization’ is modern academic publishing, in which publicly-funded science and labor is provided essentially free11 to commercial publishers who are under no obligation to return anything to the public. In my mind, this is just one of many examples of how ‘intervention’ into market economies results in sub-optimal instruments of complexity — it is in the ‘public interest’ to fund academia and it is in the ‘commercial interest’ to restrict access to academic output and to keep labor as cheap as possible. Though Apolito doesn’t go into detail about what ‘instruments of complexity’ might look like beyond the market economy, the point stands that under the market economy many instruments of complexity important to modern living seem to be deficient or failing.

“The structure of communities (the modularity properties of the network) can be regarded as the important intermediate step between the small scale of individual nodes and their local connectivity and the large scales.”

As a final point, I’d like to discuss the idea of communities as described by Apolito. Network structures happen to be surprisingly flexible; there are many ways we might relate to each other as information-sharing agents, with varying degrees of dependence and connectivity. The following image illustrates a handful of possibilities given just six nodes:

In order to have the sort of complexity we speak of when we speak of ‘instruments of complexity,’ there will have to be multiple nested layers of networks each with their own topology appropriate to the problem they exist to solve. ‘Instruments of complexity’ exist in multilayered networks, each with their own layer which features interdependencies with all the other layers. Networks grow by forming connections with new collaborators, and valuations estimate cost versus return given the particular constraints of a network’s problem space.

Let’s put that into less abstract terms by putting things into more concrete. The following is a toy example of ‘instruments of complexity’ coordinating for a public works project:

The specifics of the network design are not too important. What is important is to illustrate that each ‘subnetwork’ will have its own topology, and its own valuations — if research into material density is scarce such that some planned design is not implementable, said research should be of a higher value to encourage further research. We might call these ‘subnetworks’ communities. Communities are a familiar concept in mass politics; for example, some communities are formed around identities or common struggles in order to consolidate political power. This notion is of particular importance to anarchist groups, which see communities of free-associating individuals as an alternative to hierarchical or authoritarian political structures.

For Apolito, communities are ‘instruments of complexity’ which serve as layers within larger networks — they make possible autonomous action on a scale smaller than the entirety of the network, thereby allowing for self-organization of layers within the network. We can measure how much a community as an ‘instrument of complexity’ between nodes contributes to mutual information by the following:

What this convoluted equation measures is basically how much expected divergence there is between the two layers if we measure them together and if we measure them independently, divided by the total average of information of the two distinct layers. If there’s a large divergence given the total average of information, it means that the two layers in question are effectively more complex taken together than they are independently — simply put, their contribution is not reducible to their independent layers. This gives us an idea of how we might measure the contribution of a community to mutual information sharing between layers.

To conclude, it seems that alternatives to profit-driven markets are indeed workable provided we can overcome the problem of scale. Apolito has provided the preliminaries of a solution to said problem of scale using the notion of integrated informational complexity. That said, there might be other solutions too — they are left as an exercise for the reader.

A quick primer on the subject can be found at https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-economy-of-ancient-greece/

G.A. Cohen’s Why Not Socialism? offers a defense of market socialism.

Quinn Slobodian’s Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism is an excellent history on the subject.

Aristot. Econ. 1.1344a

“Where do these valuations come from?” you ask. The valuations are indeed arbitrary and exist to favor one product over another in order to meet certain planning goals.

One is certainly in the right to balk at the notion of using blockchains or cryptocurrencies in any alternative to market economies. In our postmodern global economy, cryptocurrency does represent an extremely egregious case of rent-seeking— but not by virtue of their technology. The fact of the industrial factory being a product of capitalism does not mean it has no place in what comes after capitalism.

Using cryptocurrency in alternatives to a market economy is a fascinating topic unfortunately well beyond the scope of this primer.

Statistical ensembles are just an abstraction by which we understand a system’s states. If we use statistical models based on empirical data to compute possible outputs, then the principle of maximum entropy states that the best representation of that model is the one with the highest entropy.

For those unfamiliar with the academic publishing business model, academics are paid by the institutions they work for and not the publisher. When an academic needs to publish their work, an article is generally sent off to an outside commercial publisher. After the acceptance of said article for publishing, the publisher charges the academics publishing fees and expects other academics to review said article as a matter of academic responsibility— academics receive no compensation for providing publishers their feedback.