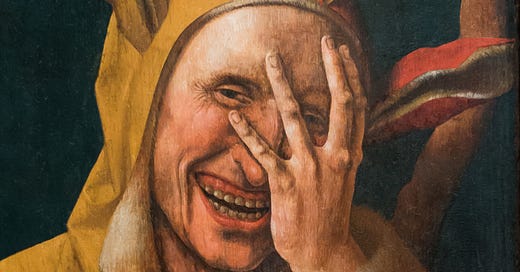

The Rough Draft of the First Page of a Novel about a Jester

The jester's name is Janeczek and his jest is assuredly finite. Do leave your critique in the comments for me.

ENTER the Jester.

—Applaud, ladies and gentlemen of the court. The king has provided us today with the finest of amusements and beauty. What a pity that it now all must come to an end. Today, I stand before you as the infamous “Janeczek;” born with slender legs and a devil’s tongue. And the contemptible voice of the shrew untamed. If the ladies of the court wish to weep, please ask the courtiers with their hands in your pockets to hand you a handkerchief. As for the gentlemen; well, I’ll address them when they arrive.

—Ladies and gentlemen of the court, there are in this world a many sorts of fools. Yes, we know of the natural fool, and we know of the artificial fool. But indeed I hope I am not offending those in present company when I say all men made in the LORD’s image are prone to the follies that have seen them be cast out the Garden of Eden. And most greatest of those said follies must be the follies of love. Learned men of that sacrum imperium indeed speak of the many sorts of love; unconditional love for one’s brother… or for one’s king, of course; on Earth or otherwise. There is love between equals such as that of friends, and the love children and parents owe to one another. Then there is the love of self, and the love of the stranger; though the Ancients call that last one ‘ksenia,’ who is surely not a stranger to the many so-called pious men in the audience today.

—And then of course, there is the most foolish love of all. Love as we know it between man and woman. And of course love as we do not know it; for those men who have felt the sting of love’s arrows in the most intimate of all places. Love, like a vengeful spirit, seems free to possess and torment anyone at will. Indeed— in the court of courtship, we’ve all played the fool. Or rather, we have been played for a fool. We strut and fret onto the stage, carrying with us everything we’ve rehearsed since the dawn of our being; with each affair, we take our place anew and lose ourselves in the role, knowing our hour is brief. And upon the stage, men and women alike: we tell the same stories, share our old worries, shed the same tears. And there in the eye of the beloved, we see ourselves reflected, a mirror as we peek over the gunwale of the boat to look at ourselves in the water. And there in the water, we see the worst of ourselves become virtuous; likewise, we become blind to the faults of she who carries that beautiful nose beneath such dazzling green eyes. Love indeed is akin to a terrible blindness, we are struck suddenly by some overbearing power and forget who we are. And in the pursuit of such, I would say, foolish love, we see knights wet their cheeks like ladies in waiting, we see troubadours turn tongue-tied, and even the fairer sex sharpens their daggers in private like stowaways aboard a silver fleet when love is at stake. Ladies! I beseech you; don’t turn your back on even the kindest of girlfriends. But I digress. On the stage of love, we do not choose our roles; merely, all of us are expected to act them, and do so admirably, or risk upsetting the highest courts. But in the acting of our roles, we take on something of the other within us. We become neither rider nor horse, but horse-rider. I mean to say that perhaps the perfect lover is therefore neither man nor woman; she is something in between, rather. The perfect lover knows every role she must play, and performs it valiantly. She is valiant and brave; she is merciful and doting. She is virtuous and commanding; she is yielding and chivalrous. And in the refuge of night, who will be there to say how a body must feel to the hand? The meeting of spirits must be a private matter, for the spirit evaporates like wax in the heat of daylight. Watch how malleable it turns in your grasp!

—And so, then…

The jester Janeczek removes a few scarves from his pocket; one is green, and the other is red. First, he wears the yellow one, and strolls confidently, his fists up on his waist. Then he removes the yellow scarf, and wears the red scarf; his demeanor becomes muted, his gaze nervous and tender. Then he holds the scarves, one in each hand, and presents them to the audience with a bow and they applaud and they knowingly nod. “The Lover,” he says. He holds up the red scarf; “the Beloved,” he says. He holds up the yellow scarf; “and the Other.” And he goes on…

—So, then, my jongleur…

Eron brought three cups of the woeful stuff to the crowded table, all full of marks and scars. He puts on before Ksenia, then one cup before Agapia, then he sits down and takes a handful of dried apples and berries. He chews, he drinks; he looks around, dazzled by the way the brilliant glow of the candles causes a shimmering glean on the greasy surfaces of the tables. He looks up at the way the aging wood seems to bulge with excess as it meets the wide timber spans of the roof. There are rough etches into the wood; of little men and animals at play. The stench of sour cabbage and belched beer hung in the atmosphere, and across from their table, a few muddy patrons gobbled up beef tripe with one carefree gulp after another. A few tables to the front, a threesome of musicians were tuning their instruments and discussing something in some foreign language. Their beards were curly, and their clothes loose and unsuited to the cold weather resting just beyond the thick, bolted doors. The woman of the threesome had her hair done up with a scarf, and her neck was buttressed by a colorful red and yellow shawl. Eron felt himself lost in a daydream, he thinks of her lonely upon a balcony; she hops, she prances, there’s a freedom in being estranged from one’s land, a freedom in being the lonely one set upon a dais.

Ksenia grabs Eron’s hand, and the private showing ends. Ksenia’s smile has a slight sorrow at the edges, but she twists it back into shape.

“Isn’t it wonderful we could come together like this? Agapia is free from her responsibilities at the manor for the night.”

Agapia took a few sips, the tint of her face turning a red ochre.

“The lady of the manor is quite kind. When you don’t cross her, of course. I try not to do it too often,” Agapia answered with a half-smile.

Eron smiled at Ksenia, and placed his hand on Ksenia’s hand. He would not meet Agapia’s gaze; Eron froze in fear of Ksenia’s petrifying eyes, with radiant amber beams that might penetrate his body. And what’s there besides fleshy betrayal, a confession that these cells were of two spirits? No; he thought of touching Agapia’s leg with his own leg, a stupid gesture of nothing. He thought: and what of eyes? A carcass strung up by the side of the shed has no lesser eyes. And won’t two pigs exchange glances across competing fences, snouts pursing knowingly, and won’t their organs whir in the sickness and pain familiar to us? And what of eyes? Pretty green eyes. Eron sees a plate of ribs pass by and his stomach churns in protest.

“Did Eron bring you those herbs like you’ve asked? I’d prepared them a few days ago already.” Ksenia asks; her grip tightens as her gaze alternates between Eron and Agapia. She looks at Eron; her green eyes are sudden struck with worry. “Yes, he did.” Agapia smiled, a few wine-stained teeth revealed themselves. “Poor thing,” Ksenia followed. “He had to walk quite a ways to deliver them to you.” Ksenia touched his face and Eron took a hearty sip; to give a worthy gift may have aroused something even more dangerous than suspicion.

—Easy now. Save the applause for later. Unwise to spend oneself so early into the night.

Ksenia bit her tongue. She was lost in her thoughts, her hateful thoughts. Damn you for your passivity, she thought to herself. Damn you all for your respective passivities. Uncertainty is the shield you cower behind. Ambiguity is the cloak you sneak in. A few older women walked by, their heads covered and their tongues lost in idle gossip. Ksenia squeezed Eron’s hand, then released and clasped her own hands on the table before her. She felt his passivity even in his grasp, in his embrace; fingers limp, still like a frightened rabbit. It seemed to her an act far more offensive than passionate dalliance; passivity denied Ksenia the catharsis she believed Eron owed her. She removed a handkerchief from her pocket and blew her nose. The role is thrust upon her; unceremoniously, she is to play the other woman without protest. She looks at the one of the older women, her aged hands pressing into a leather prayer rope. She thought of how beautiful her body must have once been; the lines and wrinkles of her face were once smooth like polished stone, a girl worth her weight. And this too was thrust upon her; that stone was an inheritance sold for the role of doting mother, and then wise grandmother. She is pushed onto the stage, given a role without knowing the words, and expected to perform in accordance to the standards of everyone else. And if she is a poor jongleur; if she falters in her roles, if she confuses a kiss for a grasp, they will let her fall. And yet, she must insist that it is within her mind; to play these roles is to pretend madness until you are overcome by it.

“Ksoonia,” she heard her sweet voice speak out. “I’ve heard from so many people who tell me they love your performances. Some of them even say it’s Bozia’s voice speaking through you.” Agapia’s smile revealed again her wine-stained teeth, dark like dried blood. Ksenia smiled, unmoved. She drank a bit of the woeful stuff, cleared her throat, then rose to her feet: “When this is done, I will go to the king, even though it is against the law.” A few of the men ceased their gorging and stared at Ksenia, who puffed up her breast. “And if I perish,” her voice slowly growing pensive and soft, “I perish.” Agapia clapped and smiled, shouting ‘bravo’ as she squeezed Agapia’s arm. “You should be traveling by tabor, educating the farmers about the LORD. Things are changing; I’ve even heard from my lady that they will be printing the Ewangelia in Polish soon.” Eron shook his head, which turned Ksenia’s stomach. “I’ll be back in a moment,” Ksenia said while stroking her belly. She stood up, and she did not look behind herself as she walked out.

Eron looked at Agapia, his fingers stiff but keeping his head still. Agapia looked down at her nails, fussing, cleaning, cutting at the edges. Her lithe fingers were full of scars from kitchen labors. They seemed both childish and ancient at the same time. He thought of opening her skull with a kitchen cleaver, to dissect the thoughts he would never know; did she think of girly things like perfume and pearls? Or was it the heat of approaching fire that burned in her breast, and the iron-stench of blood polluting her mind? He felt anger rise within him; why did she insist on these walls between them? Why did she resist his touch? He thought of reaching for her, to pounce, to entrap her in his embrace.

But it would bring him no pleasure. In that moment of her face stricken by fear and rapture, there is no pleasure. Love indeed is no mere pleasure. When Ksenia strokes Eron’s face and begs him for mercy, there is no question of pleasure. Rather, it is the exchange— of soul and spirit; of the body’s neck gladly placed upon the blade. “What I want—” my imagination, disappearing into your body, reunited with mine, untamed and violent; a willing surrender with intense joy to passion, to modesty, to some great reward. And yet, you deny me. “What I want—” as useless as a pair of eyes in a wooden bowl.

“Agapia,” Eron speaks. Her name. ‘A-ga-pi-a.’ Cried out, each syllable spells out the world: the ordinary burns away the mundane stench of dried wheat fields, and returns me to the root of you growing within me. And it is in the darkest point of night that the name will come to you. At the darkest point of night, all that has been aroused but dormant in day asserts itself. It cries out in dreams, or in the prayers before bed— it cries out like Ksenia’s voice in the most intimate of moments. “Please!” When they are unattended, or unrestrained by ritual, they nervously fret, they itch: they trouble your sleep, and haunt your waking hours with paranoia.

And then you awake to the terror of sunlight. Mornings are relentless, and burn out the grief of night. In the mornings, nothing hides, and nothing reveals itself either. And we look to each other, our eyes meet, and we question whether there is such thing as a bond at all; we are stupid, we are blind under such caustic light. Passion flees for the darkness of the trees up the hill but it leaves behind its twin faith, and torments and taunts the mind with the relentless and unarresting doubt that all true faith must bring. Everything in the body but the body itself stirs. And Eron turns onto his side, avoiding Ksenia’s gaze.

“Agapia,” Eron speaks. Agapia looks up from her fingers. She is harsh, unyielding; she demands nothing and demands it without condition. Her eyes search around Eron; a looming sadness drags at the edges. She blinks. She looks Eron in the eyes; her face softens, and the slightest smile breaks. You fool; don’t overdo it. And where have we met before? Her brilliant eyes flicker only for a second before she looks away.

When Ksenia returned, the music had started. Some had taken their chairs to come closer to the short stage. The woman in the colorful red and yellow shawl removed the scarf from her hair and waved it about, and she stepped with half-circles. The two musicians looked at her, and looked at each other, and they started to play a familiar melody— first in concert, then in alternating movements to leave no gap in the air. When she approached the table, her shadow grew impossibly large and loomed over Eron and Agapia. She saw their bodies stiffen, and Eron turned to meet Ksenia’s gaze; she felt like some terrible giant striking terror into the stupid inhabitants of a village. She approached the table and drank all of the woeful stuff she had left in her cup, and she drank some of Agapia’s for good measure. Ksenia reached down and tied the edges of her tunic and gown together, and fastened them above her knee. She studied the edges of her shoes; a few strands of felt stuck out from the sole. She tightened her belt and took a deep breath.

Ksenia approached the short stage. She curtsied to the woman in the colorful red and yellow shawl, who curtsied back with a smile. Ksenia held her waist with one hand, and raised the other above her head, and she twirled steadily and carefully between the chairs, and she rode the music like a flower in the wind. The woman in the colorful red and yellow shawl clapped a few times, then she sang:

Thus I begin

a new little tune

in which I enclose and bind

a plain song,

Ksenia lowered her hand, and now had set both of her hands to her waist, and she would interrupt her steady twirls with steps; one on the edge of her toes, another on the heel of her foot. Two of the older women approached the short stage— they held each others hands above their heads, and made delicate steps beside Ksenia. And she sang:

for more difficult verses

make dunces deaf.

Ksenia stepped on the heel of her foot, then hopped on her other leg to bring the heel up behind her back, imagining herself the shape of a doe as it leaps over tall grass. Then she would drop the leg, making a loud crack, and hop on the other one to make another step on the heel; the shape of a stork, standing in tall grass. It was the dance she’d seen her mother do, there ‘tween the crack of a door; she would dance, and she would sing and she would play gusli to herself and she thought she was alone and she deserved some great thunderous applause and Ksenia would close the door and walk away. And she sang:

if my heart were merry;

but I shall change it, since everyone wishes so.

And then Ksenia steps on the toes of her foot, then twirls, twirls again; her hands are stiff in an embrace of the air. And she makes a tender leap; her arms extend, like a bird taking flight. She feels the ground slip beneath her soles; she twirls, twirls again. A few curls of her black hair fell down onto her face. A terrible tightness presses in her stomach; she presses her hands up to her waist and tries to smuggle in one labored breath after another. Two of the older women danced in circles around Ksenia, their calloused hands clapping along to the melody with such force that her ears filled with dizzy bees. And she sang:

So sweet is

my heart when it flares

Ksenia bowed, then kicked her feet along to the music by means of small intricate patterns; a kick to the side and to the back and to the front, in a cross, in a circle, knees raised then a sudden plunge, arms extended like branches, maddening and loud like a stampede of horses rampaging beside the Dnipro. Horses; horses… Ksenia sees the hills appear beyond the rushing rapids; the soil turns to runny mud beneath their rampaging hooves. Horses; horses, and Ksenia whinnies and whines, and jumps up, and buckles ‘neath their weight. Horses, horses. And she sang:

it makes me then bleak

when I sadly consider

And Ksenia hopped, and she rattled her head, and her braids came undone and whipped and flagellated the air, and she is whispering to the air ‘you must feel this somehow;’ with hoarse throat, she dropped to her knees, and the’s all bruised and bloodied now, and she claps for the two older women who take the shape of Afrodyta, the shape of Eufrozyna— they oppose each other under the sheen of the wooden candles, wax dripping on their dirty toes, gentle and yielding as stone melts to liquid. And they turned; they twirled and twisted like coupled snakes in mud. And she squirmed and flopped on the floor like a dying fish, and she jumped up, and she groaned in pain— a few spurts of blood streaked and freaked over polished wood. And she sang:

"I have a foolish heart

for I only love alone and without solace"

Thus I turn my pleasant thought into grief.

And then we let memory speak. Her neck is slick with sweat. Beside the cold, rushing stream, a few dolls floating beneath the foam and the moss. The words may come to you easily, but they never leave without great struggle. A few flames hung above them in the trees like sleeping phoenix, with bellies fat on lardy bread. And the gut strings sing so forcefully, they screech. And I’d bitten him on his arm, not too harshly, for what he’d said earlier down by the pier where they’d released the garlands and we’d spied on the girls as they had their fortunes told and we’d parted the mallow and the cornflowers and they’d set the candles upon little lonely islands drifting in the great empty valleys of flowing water and I’d said ‘if you’d find one, would you think of me’ and he said ‘I would not’ and I’d chased him down endless fields of blossoms which shuddered like living pelts in the breeze of summer, I chased him down the endless rows of wheat which swayed along to the endless chanting, and I chased him down beside the creek and I wrestled him down to the ground by his legs and she sang ‘So sad is’ and I wrestled him down onto the grass rolling and rolling and he did not resist and she sang ‘my heart, by Christ’ and I was panting and I was wailing and I said ‘please show it to me now’ and I smacked him on his face and I boxed his head and I punched his shoulder and we spun and he pinned me up against the cold mud and I felt his weight press down upon me and the sweat formed around his lips and his eyes and it dripped onto my face and she sang ‘that I am a total lunatic —’ and he pulled up my tunic and he trampled my wreath and he unfastened me and I shouted that he was a devil and that he was a villain and I pushed him off of me and I ran down the creek holding the edges of my skirt with my hands and I ran down the creek with tears in my eyes, laughing so hard I could barely muster the breath to escape him, and I entered the water to hide among the reeds and I heard him whine and cry and scream with worry and the rain came down onto my back and my hair became a heavy and sullen rag and I ran into the water and I shouted that I would rather die, that I would rather drown, and that I never ever wanted to see him again and she sang ‘for now I’m in pain’ and I trashed in the water and I howled and I raved and he ran after me and he could not swim and he pulled on my arms and he shouted for mercy and for grace and for help and I dragged him deeper down into the water and he could not breathe and I thought of him drowning and I screamed that I would join him right there and then and he fought me and he pulled me by my hair and I pulled on a few reeds and a few stalks and a few branches and the water began to rush and I felt the branches break in my grasp and he pulled on my shoulders and he gasped for air and I felt us tumble through the water and I felt us thrash across pebbles and stones and the water took us for a few seconds in a frozen embrace before spitting us back down onto the cold mud with the sun burning on our faces and he was coughing up water all over himself and I crawled over him and I smacked his chest and I kissed him once and I kissed him again and she sang ‘and now suddenly joyous;’ and I smacked his chest and our clothes were heavy with water and he looked up at me with his eyes and I thought of how I must have looked with sullen cheeks and blue lips and hair like a damp cloth and body slick’d like a fish and he kissed me and he kissed me again and again and I said ‘yes, yes, yes, yes’ and he tasted of swamp and moss and he undid my belt and he pulled up my tunic and he unfastened me and he pulled me aside and he straddled me and he took me there first gently and then violently and she sang ‘see how it turns me now wise, now mad.’ And he grunted and panted, and I felt him throb in my grasp, and I felt his heart leap, and he kissed me and he kissed me and he said ‘please don’t leave.’ And she thought of leaving and she did not. And the rain started again, a field of little drums surrounded them. And she said to him ‘would you always think of me as I am here now. Even when my face is worn like leather, even when my hands are swollen and rough? Would you always think of me as I am here now?’ And he leaped up and he said nothing and he kissed me again.

After the music died down, the muddy patrons rose to their feet and applauded with their cracked hands slick’d by grease. Ksenia wiped the sweat from her forehead and took a seat beside the stage; one of the musicians handed her a handkerchief with a gallant smile. She wiped her face, then her bloodied knees. She kissed the older women who danced beside her, and she touched their hands; harsh like straw. She saw the quiet burn between Eron and Agapia, neither of whom would meet her gaze. The musicians looked to each other, then to the woman in the yellow and red shawl who nodded and waved with her handkerchief. She stepped forward on one foot, made a semi-circle, and the music restated the opening theme; and she sang:

I can't recall

anything about her – know that –

except once when I saw her and she held me.

Thus I begin…

—Thank you. I love you all foolishly.