“When the real is no longer what it was, nostalgia assumes its full meaning.” —Jean Baudrillard

I.

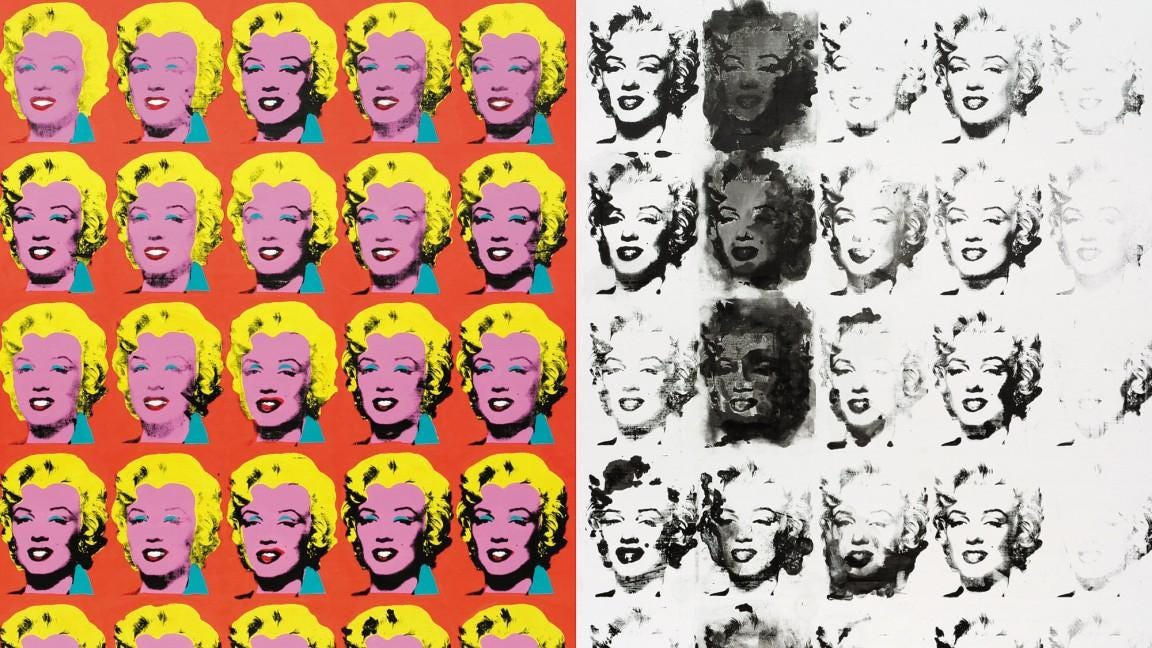

I’m walking through the MOCA’s Sturtevant exhibit, and I get a little surprised seeing a Warhol hanging on the wall. I approach slowly, smiling like one of the many Marilyn Monroes in the painting before me. With each step however, imperfections start to reveal themselves in their faces. Some of the Marilyn Monroes are smudged, others missing the sharp contours that defined her beauty. There are a couple of Marilyn Monroes so faint, you only see them once you get real close. Each little face is like an individual in a collective or a single frame in 16mm film. It reproduces into something new, but never loses its coherence, its connection to what spawned it and gave it purpose.

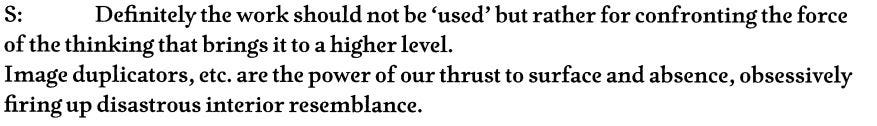

Sturtevant did her “repetitions” by memory, in the hope of capturing only the surface of what she reproduced. The work is much more radical than Warhol’s pop-art — she made the surface of Warhol’s piece the art work itself, and it exists only on that surface. If I hadn’t seen Warhol’s original, Sturtevant’s repetition would cease to be a repetition and the art work would disappear into the surface she’d reproduced. She anticipates a culture of art that would follow thirty years after, obsessed with surfaces to the point that the separation between surface & the art work has disappeared.

Watching the “repetitions,” I thought of Adorno’s “melancholy of form1.” Everything outside of the form of Sturtevant’s repetitions is obliterated and only the longing is left. The context of Warhol’s originals becomes irrelevant, and all interior dialectic is resolved. Material and content converge to create an imprint of what was remembered — the truth-content is the memory of the original art work itself, sentimental for “utopia without betraying it to existence2.”

I’d hope to exorcise the sorrow of these repetitions, these surfaces from the so-called hauntologies of Derrida via Fisher, who elevated nostalgia for the modernist cosmopolis to a political project predestined to fail3. The repetition speaks of not of a lost dream but of a trauma, an absence we can’t identify4 even though it haunts our desires. Building mythologies from the rubble left by previous civilizations is nothing new, but the proletariat gets misty-eyed for more than just lost futures when they fill seats for an Avengers film. The desires they mourn are not purely cosmopolitical — it is libidinal too. Fisher’s ghosts are not egalitarian social democrats, but violent daemons who provoke us into terror and seduce us into depression. Such is the power of the surface.

II.

“Ah shit,” you’re probably saying, “I bet this is gonna be about vaporwave,” or James Ferraro, or Oneohtrix Point Never, any of the many scavengers of mass media’s golden age during the 80s-90s. Repetition, hauntologies of the past, Derrida & daemonology — must-haves for the bingo chart when they read out PR copy for an experimental album. If Musiques du monde was the post-colonial sound of reconstructing the former colonies from a surface, vaporwave was the post-post-colonial sound of reconstructing Empire itself. You can’t blame Mark Fisher for missing the days before middle-class posers went to college, when the slogans were to the point and unencumbered by French loanwords. Life was yet unencumbered by the weight of knowing the world.

But as a cultural expression of melancholic longing, the potency of the ‘vaporwave’ meme cannot be denied. With their fat portfolios in hand, the vaporwave kids found some gainful employment with the exceedingly-fewer corporations that continue to tighten their stranglehold on mass media. What started as a loose conglomerate of Tumblr blogs and Bandcamp links has been successfully Balkanized to fulfill marketing niches — something-wave + anime opens the EDM market to Drive fans while “Lo-Fi Study Beats” is revisionist history for college kids too square to know DJ Screw. Several Reddit pages canonize the sensuous partnership between technology and mass media art in the 20th century, before profit margins pointed the way towards a minimal monoculture. Entrepreneurs are thinking of ways to ‘remix’ architecture. Considering its quick adoption by the culture industry, it’s surprising to see vaporwave described as a “Neon Anti-Corporate Aesthetic.” — when I wrote this in 2019, the packaged retro-futurism of NFTs were but a glimmer in tired eyes.

But this is no apologia for vaporwave — for that, check out this hoax video filmed at my parents’ house. Rather, I’d like only to point out a quality of our longing. Popular culture is essentially stuck in its own feedback loop; constantly gobbling up its own past and regurgitating it as consumers try to figure out what exactly is missing that generates so much longing. Generation loss has already set in, the physical substance continues to degrade and loses resemblance to its surface; we’re archaeologists of own past, failing to make sense of our collective experience one hazy memory at a time. Culture ain’t dead, it’s undead.

If you really want to understand Far Side, first off, listen to [Claude] Debussy, and secondly, go into a frozen yogurt shop. Afterwards, go into an Apple store and just fool around, hang out in there. Afterwards, go to Starbucks and get a gift card. They have a book there on the history of Starbucks — buy this book and go home. If you do all these things you’ll understand what Far Side Virtual is — because people kind of live in it already5.

Originally conceived of as a series of ringtones, James Ferraro’s Far Side Virtual is to me the most accomplished art work of the ‘vaporwave canon.’ Like the ringtone itself, it assaults the air, somewhere between pleasant and alarming. It’s haunted by cybernetic refuse, a trash monster that has reconstituted itself from abandoned digital runoff. It’s all surface — like Sturtevant’s repetitions, Far Side Virtual would disappear into its pristine synthesizers and computer rhythms if the listener didn’t share its melancholy for a forgotten world that uncomfortably sits in the ambiguity between utopia and dystopia. It’s the perfect soundtrack to Second Life’s perverse Lego Land, daemons lurk underneath the surfaces as Far Side Virtual’s sterile soundscapes quickly become eerie and unnerving. This is the dialectic of cyber-punk: Eden subverted by its own inability to fulfill itself. How quickly our dreams become nightmares, desires become obsessions, pleasure becomes pain. The radical posturing of cyber-punk is its own facile surface; this is post-revolutionary blues music.

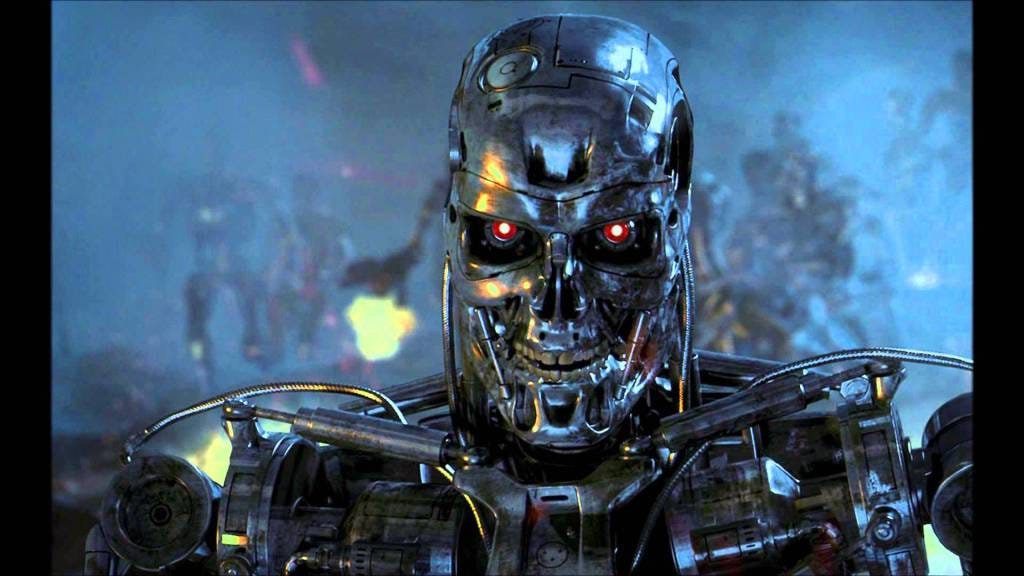

Mass media art of the 80s-90s was obsessed with the lurking of daemonic forces underneath surfaces. As technology made home-video possible and special effects better, film became even more violent and gory as enlightened technocracy gave way to hedonism’s bloody spectacle. Terminator 2 is, I’d argue, a defining influence on our imagination of the struggle between secularized technology and pagan daemons. The T-800’s humanity is only a skin that hides a daemonic force under its surface, an undead skeleton with glowing devil eyes. It’s the perfect expression of a modern fear of machine autopoiesis — machines becoming self-generative and autonomous invites evil, which festers without ritual purification. The upgraded T-1000 presents an even more base threat — technology is truly evil if it can adopt any shape, mimic any object, without the pretense of being organic and mortal.

The T-1000’s amorphous surface was a prescient prediction. The earliest vaporwave artists were keenly aware of the dialectic they engaged with as sampling, piracy, recycling digital refuse, and glitch all represent a drastic disavowal of the material logic inherent to the subject matter they drew from. Mass media of the 80s-90s reified only the surface to boost merchandise sales but once that junk got pushed into the landfills, you were left with pure Spectacle — “a social relation among people, mediated by images.” The images need not follow material logic; in anime and Second Life, sexual characteristics become impossibly inflated. Slasher flick gore, lovingly celebrated by videogames, turns the fragility of the human body into a surrealist sculpture. Eccojams take lyrical fragments and repeat them until the words dissolve into their own psychological import — the inspired comments gleefully drinking the resulting liquid down.

Cultural substances through this process have become their surfaces, and how we experience them has shifted from an event happening in physical space to repetitious & amorphous presences. To speak of culture as being material now seems like a joke, vaporwave mocks the mere physicality of sculpture. The techno-optimist frames this as individualistic liberation — concerts just for you on your phone, film when it’s convenient for you, and art on tap from any niche you choose to opt-in for6. The loss of this physicality leads to pure sensuousness, though in a form muted by the medium which always introduces loss as a product of its form.

Surrealism inevitably develops as a response to this loss as a method of recovery; the most sensuous aspects of the physicality depicted (blood, sexual organs, nostalgic signs) are amplified until they consume the entire surface of the art work, but the medium always fails to satisfy the physical urge that caused the need for that depiction. Out of melancholia comes a paranoia — something is missing from the image but I don’t know what it is, all I know is that the absence is there. Our reaction to the work inevitably becomes a matter of urge; to reconcile and to recover what was lost. Positive feedback occurs, increasing sensuality and exaggerating the properties of its surfaces as it distances itself from the physical Real — this is why vaporwave is uncanny, the territory rots but the map persists.

III.

You raise your arms indignantly: “Are you serious when you use the word ‘daemonic?'” It is definitely not le discours de mode to speak of such non-secular terms in art — ‘daemon site:pitchfork.com’ in Google offers few results. Yet to speak of pure material when referring to things such as repetition seems like a futile effort. Indeed the historical connection between the daemons of pagan traditions and repetition is itself ancient, so powerful that even the dominant religions who spread themselves through purification could not rid themselves of it — Islam, Christianity, and Judaism all maintain repetition and its ensuing trance as part of their spiritual history even if banished to ‘esotericism.’ I don’t believe this aspect of human experience can be ignored when speaking of our culture’s taste for necromancy, where the spirits of the past are conjured to reveal something about the present & future. Necromancers of the ancient times were themselves even keen of repetition when performing their rituals. Instead of reviving corpses, we’re reviving surfaces.

“Let’s not get too cute,” You protest. “To withdraw into cliches about zombies and skeletons is just dodging the problem.” I agree but look past the myth, find the cultural process it signifies instead. This is the ancient ‘magical’ aspect of mimesis which identifies with and reproduces ‘blind expression,’ far predating European art’s rationalist tendencies7. When the dead is raised, only its decaying sensuousness remains as its spirit is made perverted or daemonic by its resurrection. I argue this mimetic aspect is dominating our current mode of cultural engagement, enabled by technological advances that have not only made death impossible for cultural artifacts but in fact negated basic physical facts about death itself.

This is why I must use the term surfaces when speaking of cultural artifacts or art works, to acknowledge and assert that indeed a massive change in our engagement with cultural artifacts has occurred. Owning surfaces is an inherently an absurd concept — if only I’d known in 2019 that this absurdity would reach a fever pitch only a few years later — for they are endlessly replicable without loss to whatever arbitrary data is deemed its original. This was the great innovation of Sturtevant’s work, prefiguring the postmodern artist as a curator of surfaces she gathers from other sources. Deleting a surface cannot mean physical death, for nothing physically changes except the organization of a few electrons. Even then it may still reside in memory, in the file system, or across a global network of servers and clients. The paranoia I speak of only increases on social media, where everything is between an uncertain flux of existing and non-existing — context, meaning, joy; something has to be missing from this image, but I wouldn’t even know how to recover it. We don’t know what it is we’re mourning, nevertheless we are mourning it8.

Paranoia of what may be missing, melancholy for what was lost leads to necromancy by means of repetition, provoking the daemons to bring themselves forth from surfaces and afflict us with retromania. It should be no mystery why the most shudder-inducing perversions of technology’s secularized world invoke humanity’s pagan roots. Synthetic androids somehow being imbued with a human’s ‘soul.’ Gods apathetic to human morality arising from machine processes that are slipping out of our control. Young women turned into idols worshiped with religious devotion by the masses, or turned into icons. The purifying eschatology of global climate change, here to punish us for our gluttony and apathy. If you find it all hard to believe, submerge yourself in the salty waters of a warehouse party and allow the repetitive music to induce its magic. It’ll obliterate any doubts. Out of Christianity’s corpse, the spirit of what it failed to eradicate will rise again — there are no theists in raves.

Aesthetic Theory, pg. 144

Ibid, pg. 132

Like his musical heroes, Mark Fisher saw great value in masochism as a rhetorical tool. Deprecating himself for being a white male was not simply a political gambit. His tragic suicide was a poignant closing remark to his writings — an Ian Curtis to the exhausted Berniecrat.

As Freud puts it: “he knows whom he has lost but not what he has lost in him.” (Mourning and Melancholia, pg. 244)

Conservatives thought the pornographization of popular culture meant masturbation on Sesame Street, but what it really meant is reducing every experience down to its particular fetish — seeing feet when you search for MILF is symptomatic of a faulty delivery system.

See pg. 362 of Paddison, Max. “Adorno’s ‘Aesthetic Theory’.” Music Analysis, vol. 6, no. 3, 1987, pp. 355–377. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/854210.

“We are not aware of this, nevertheless we do it.”

it’s not quite the same thing, but your essay makes me think of the myriad ballroom jazz / big band / blue-eyed soul + [atmospheric sounds] + corny description channels that are big on youtube right now.