2020, Belarus. I’d just gotten off the plane from Yerevan, standing there in line at MSQ in Minsk for customs besides the other Armenians. Tensions were high as just over a week ago on the 12th of July, 2020, Azerbaijan and Armenia had a clash that resulted in the destruction of an Azeri vehicle. This clash didn’t occur in Nagorno-Karabakh however, nor did the other skirmishes that would follow through the rest of July. In our shibboleth of Armenian, the people I stood with expressed their worries and concerns— maybe the conflict was coming to Yerevan this time. A portly man who lives in Germany but came to support his family during the COVID-19 crisis wipes the sweat off his forehead. “Another war will probably start again.” Soon the discussions turn animated as they talk about what they’ve seen on Facebook, and if anyone in their family is in the military. The portly man gets loud, prideful when he speaks: “why should I send my son to die for them? They don’t do anything for us!” A woman gets indignant and cries out: “you’ll let the Turks kill us again.” The portly man wipes the sweat off his forehead again. In public, Armenians are proud nationalists but in private they let their vulnerabilities and fears show. Another woman pointed at a group of black-haired, olive-skinned people coming through the same doors we did— unmistakably dressed in the drab clothing of post-Soviet states. In Armenian, she said: “look, these people must be Armenians too.” The portly man demurred, “Armenians don’t have green passports.” A clear implication, they’re from Azerbaijan. Everyone hushed and turned their eyes away.

To begin, I’d like to make clear that the purpose of this essay is not to evaluate claims about Nagorno-Karabakh, nor to adjudicate a history between Armenians and Azeris that has turned from mutual cooperation, to peaceful coexistence, to conflict and back, many times. Neither is it to reproduce propaganda about what either side has done or not done; mere fact has no protagonists nor antagonists, and there is no clean war. It is up to historians to moralize about Armenia and Azerbaijan. Rather, I’d like merely to offer an alternate perspective to a simple question: why are Armenia and Azerbaijan fighting over Nagorno-Karabakh? Why now? I’d like to dissuade you from the simplistic conclusion that this is a localized nationalist struggle over irredentist claims, and instead make three arguments:

the belief that the conflict is entirely rooted in a historical struggle between Islamic Turks and Armenians is tempting but flawed. Azerbaijan’s alignment with a greater Turkic world is strategic, and arose after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The Azeri people of both Azerbaijan and Iran have a nuanced relationship to the greater Turkish world, and Azerbaijani nationalism cannot be reduced to pan-Turkic or Islamic nationalism.

the current Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is not fueled by ethnic tensions or irredentist claims, but rather by conflicts in interest caused by Azerbaijan’s burgeoning gas and oil production. Nationalist rhetoric obscures the fact that Nagorno-Karabakh gives Armenia leverage over Azerbaijan by allowing it to threaten gas and oil exports to Turkey, the EU, and Israel, all of whom seek to reduce their dependence on Russian exports.

the root of the conflict is economic; a global economy suffering in the wake of COVID-19 and intense foreign interest forces Armenian and Azerbaijani confrontation. However nationalist rhetoric makes this opaque, both to those on the outside of the conflict and those involved in it, thus the cause of the conflict becomes mysterious and the only rhetoric that remains viable is nationalism.

Much of the rhetoric surrounding this conflict stresses historically violent ethnic and territorial struggles. For Armenians there’s been a longstanding desire for resistance against the multinational Turk, motivated by the conviction that the 1914 genocide of Armenians in Ottoman Turkey never really ended. On the other side, Azerbaijan found itself feeling persecuted for its own Turkic-ness, even though the relationship between Azerbaijan and Turks of Turkey has more nuance than a simple “brotherhood of Turkish nations.” For both nations, these ethnic narratives are a reliable way of drumming up support both domestically and internationally— memories of a fallen Constantinople (Պոլիս, or “Polis” for Armenians) still haunt the imagination of the Christian West, while pan-Turkish nationalism appeals to people who feel a common lack of identity in the aftermath of Soviet collapse. These narratives are attractive because they give the impression that the conflict exists ‘outside’ of history, permanent, and thus any action that follows can be explained as inevitable or justifiable. It is telling that when I ask Armenians about the conflict, what comes to mind is not the numerous geopolitical motives Azerbaijan might have for attack. Rather, it is the massacres and memories of genocide— the historical Turk and the historical Armenian are doomed to be rivals. Likewise for Azerbaijan, where in 2012 Aliyev suggested an international Armenian conspiracy against Azerbaijan:

First, our main enemies are Armenians of the world and the hypocritical and corrupt politicians under their control. The politicians who don’t wish to see the truth and are engaged in denigrating Azerbaijan in different parts of the world. Members of some parliaments, certain political figures, etc. who live on the money of the Armenian lobby. (Aliyev 2012)

Moreover, it is Azerbaijan’s foreign policy to further pan-Turkish goals. At the Tenth Summit of the Turkic-Speaking Countries’ Heads of State, Aliyev said:

The Turkic world is large. Since Zengezur, an ancient and inseparable Turkic land, was taken away from Azerbaijan by Armenia, the geographical continuity of the Turkic world has been lost. If we look at the map, we will see that if this historical injustice had not taken place, today we would have an integral Turkic world from the geographical point of view. However, geographical coordinates are not the only things that unite us. Our relations, brotherhood, and common past and present provide our unity.1

Here, one might be seduced into an ever-ending debate about what land belongs historically to whom. Is Nagorno-Karabakh Turkic or Armenian land? This debate is unlikely to ever end; populations never stay static, they evolve as borders do. I believe it’s more instructive to ask instead what the purpose of Aliyev’s statement is. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the loss of security and policy unity this union once offered, the government of Azerbaijan has sought to align itself with Turkey, going so far as to place the Ottoman crescent on its flag— a bold move as the Ottoman empire was a Sunni empire and Azerbaijan is second to Iran in number of Shi’ites. “Azerbaijan” as a name is not even Turkic in its etymology, but rather Persian. This is not merely coincidence as since the fall of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan has undergone a remarkable change in its religion and national character:

Whereas in 1976 there were 16 registered mosques and one mädräsä (Islamic school) in Azerbaijan, there were at the end of the Soviet period already about 200 mosques, and until today this figure has increased explosively to more than 1,300 mosques, innumerable Islamic schools, a working Islamic university, another, financed by the Saudis, in preparation and a Turkish sponsored İlâhiyat Fakü-Itesi. The phenomenon of a “religious renaissance”, taking place in parallel with a “national rebirth” or “birth”, is a fact which cannot be ignored. (Motika 2001)

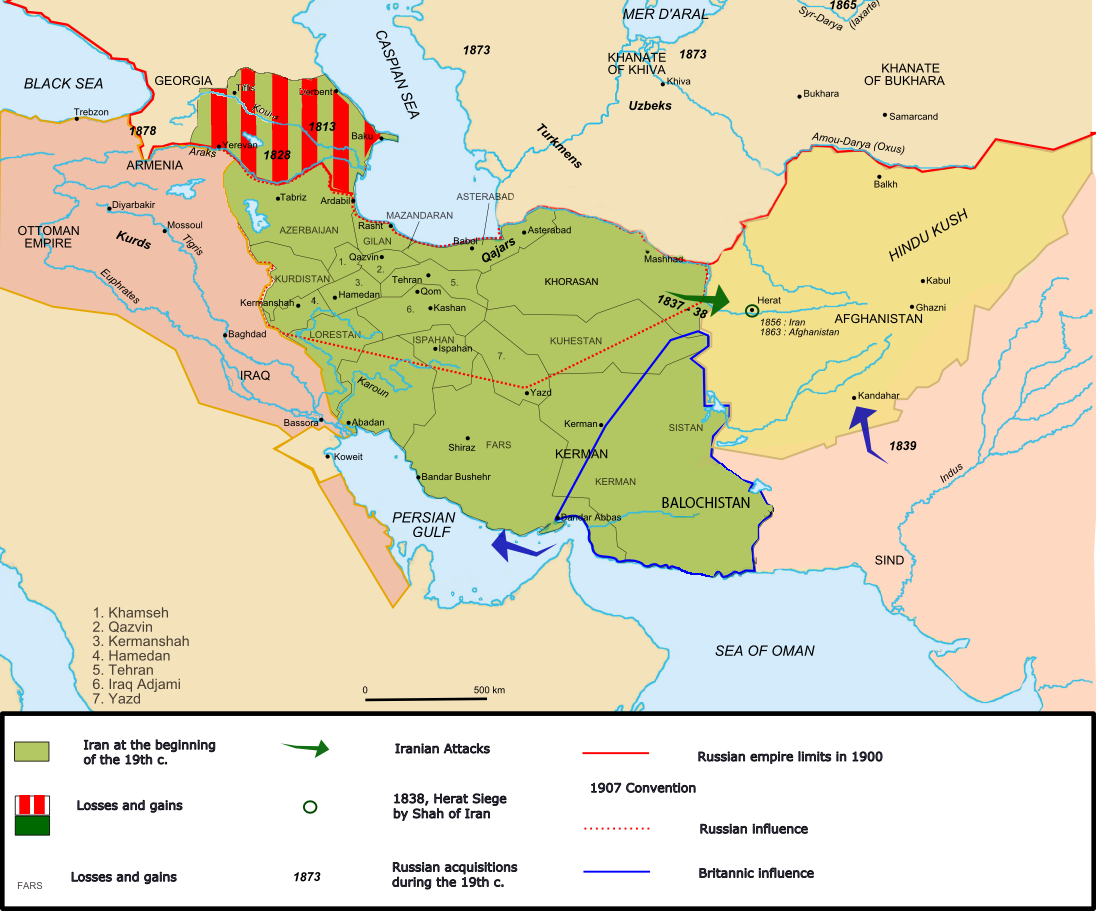

The question of Azerbaijan and the Turkic world is even further complicated by the fact that the majority of Azeri people do not live in Azerbaijan, but in Iran. And in contrast to Azerbaijan, the Azeri people of Iran did not consider themselves part of the Turkic world— attempts by the former Ottoman empire to inspire within them nationalist sentiments based on the supposed geographical continuity of the Turkic world failed. (Atabaki 2001) Taking historical record into account, the Azeri people both in Iran and Azerbaijan have strong linguistic, historical, and ethnic ties to the Persian peoples and its varied empires as much as all people of the Caucuses do. Yet the Azerbaijan government distances itself away from these ties in favor of stressing its place in a Turkic world.

Therefore one should not read Aliyev’s statement about the geographical continuity of the Turkic world as a statement of fact, but rather one of ambition. Azerbaijan hopes to identify itself with the Turkic world on strategic grounds, despite ethnic and religious traditions that tie it to other peoples of the Caucuses and Iran. Unlike pan-Turkism, pan-Iranism did not emerge as a powerful force in the post-Soviet era, leaving Azerbaijan with either the choice of continuing an alliance with economically-decimated ex-Soviet states or seek other alliances. In addition, as historical Shi’ites and religious moderates who reject mixing religion with the political (Motika 2001), Azerbaijan could not be a part of the global Islamic nationalist movements that rose at the same time. Therefore, pan-Turkism likely felt like the only viable identity as the idea of a brotherhood of Soviets collapsed.

I should be clear that my point here is not to suggest that the Azeri people are not Turkic or that Azerbaijan is not part of a Turkic world. What someone chooses to identify with is ultimately precisely their own choice. Ethnic ties such as these are abstract and always subject to change as power and culture changes, and claims about Azeri people being Turkish are no different from claims that Germanic people are German or the many tribes of America are Native American. Rather, I hope to put into context Azerbaijan’s Turkic nationalism and show that it is a modern project that developed in response to geopolitical changes that occurred in the aftermath of the Soviet fall. From this, I believe there are two major points to be considered:

—firstly, Armenian sentiments about Azeri people being Islamist Turks with which they’ve been locked in a struggle since the Ottoman empire are misleading and ultimately play into the ambitions of Azerbaijan’s government to be part of the Turkic world. Armenians are amongst the many ethnic groups native to the region known today as Iranian Azerbaijan and have close historical and ethnic ties to the Azeri people. Narratives about the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh being a historical struggle against the Islamist Turks belies this fact. Neither the Azeri nor the Armenian claim to land supersedes the other.

—secondly, claims by the Azerbaijan government about Turkic land are self-defeating as the question of who the “Turkic peoples” are is still unanswered with regards to the Azeri people. If the Azeri people of Iran do not consider themselves Turkic and therefore have no rights to the land on which they are native to, then Azerbaijan defeats its own nationalist ambitions. If parts of historical Armenia are parts of the Turkic world, then by definition Armenians would be native to the Turkic world, in which case Azerbaijan also defeats its own nationalist ambitions.

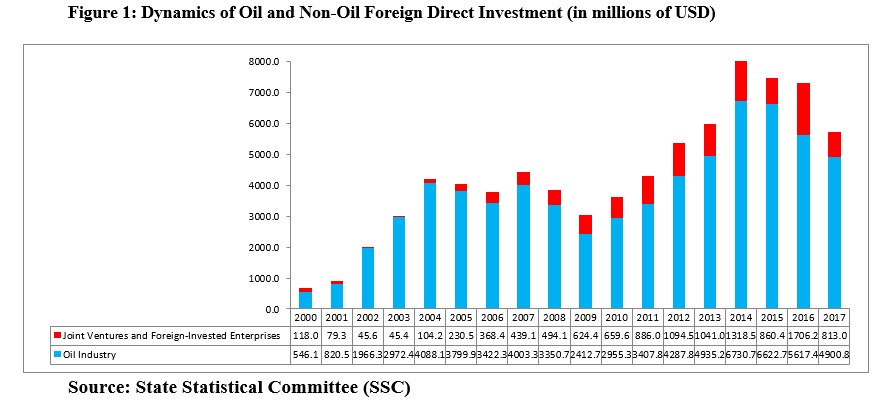

Rather, I offer an alternative. The government of Azerbaijan’s pan-Turkic Nationalism and its rhetoric with regards to Nagorno-Karabakh are based on post-Soviet economic and political motives, and not reducible to hatred of Armenians or even a desire for Nagorno-Karabakh itself. Likewise the Armenian government leans on ethnic tensions between Azeris and Armenians to mobilize against Azerbaijan, and prevent it from dominating the region and therefore leave a landlocked Armenia politically and economically isolated. Azerbaijan with its oil and gas resources is projected to become an economic powerhouse in the Caucasus region, constrained only because of a lack of equipment and expertise necessary to make use of its resources. Armenia on the other hand is the smallest economically of the region, not having the production of resources necessary to ride the oil boom. As a matter of fact, 95% of Azerbaijan’s economy is mining and energy which makes foreign investment, privatization, and security key motivations for the government of Azerbaijan. On a global scale, those countries seeking an alternative to the oil and gas of Russia and OPEC have tremendous interest in Azerbaijan. This means that when Azerbaijan acts, it acts with global interest and investment into Azerbaijan as its priority.

Why is this of importance? I’d like to return to that previous speech by Aliyev, delivered at the the Tenth Summit of the Turkic-Speaking Countries’ Heads of State:

Today my dear brother Abdullah Gul noted that we are working together on energy security. This is an issue of special importance in Turkish-Azerbaijani relations. The region has benefited from the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan and Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum oil and gas pipelines. Natural resources are being transported from the eastern shores of the Caspian Sea thanks to the opening of these routes and corridors. Today, oil products from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan are conveyed through Azerbaijan and Turkey to world markets. I am sure the benefits of this cooperation will continue to grow. There is great demand for multilateral collaboration in this field. The Caspian Sea is rich in natural resources. Turkey is a large market for us and this fraternal country also has great transit potential. Strengthening our efforts in this direction will, in turn, strengthen every country. (1)

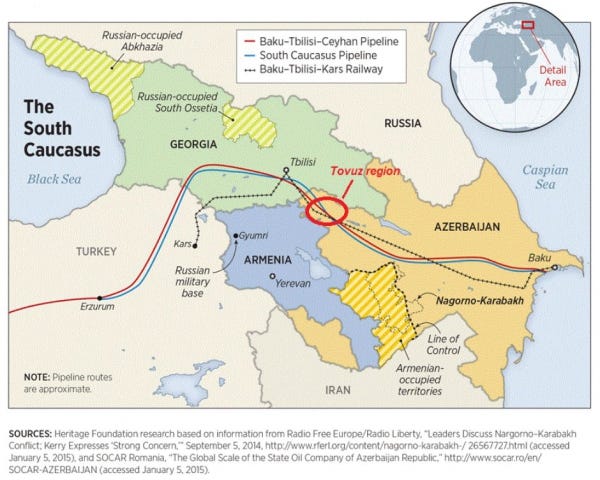

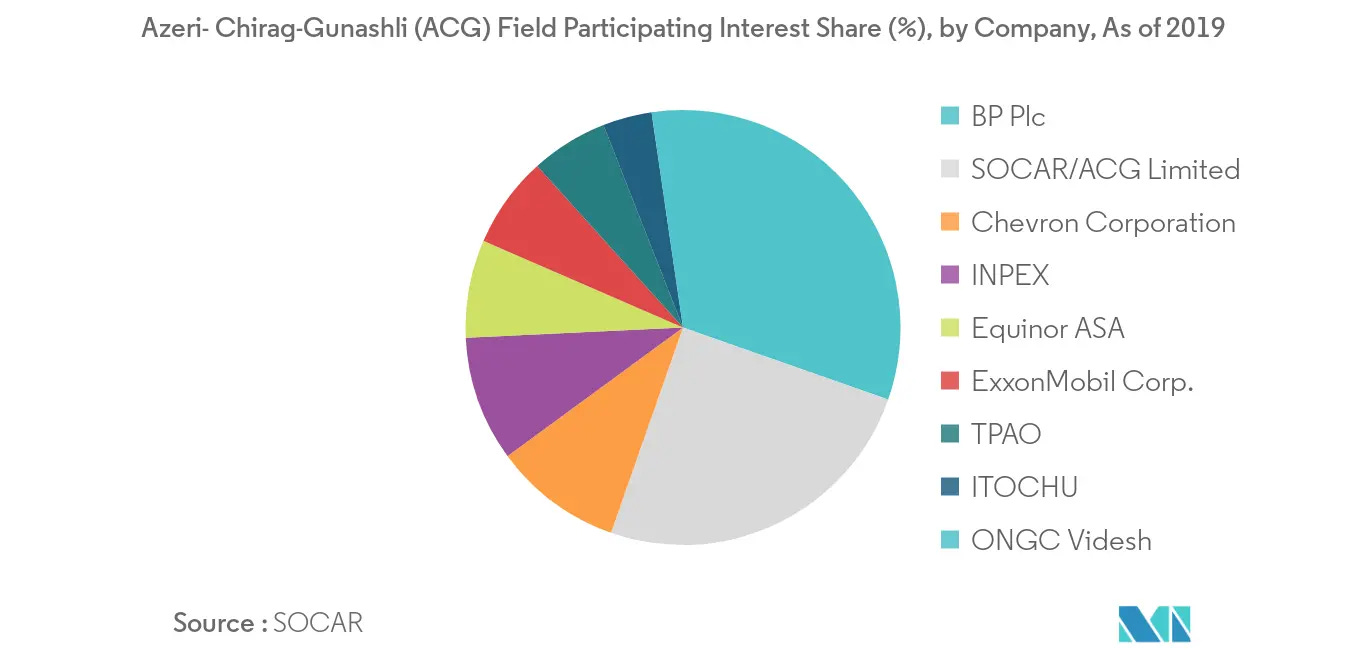

One cannot underestimate the importance oil and gas plays in Azerbaijan. The current president of Azerbaijan, Ilham Heydaroğlu Aliyev, was the vice-president of SOCAR for many years, Azerbaijan’s state-owned oil company which formed the Azerbaijan International Operating Company with foreign investors such as BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Türkiye Petrolleri Anonim Ortaklığı2. In his speech Aliyev refers to two pipelines stretching from the capital of Azerbaijan, Baku, to two Turkish cities. It’s no secret that Turkey has been seeking to reduce its reliance on Russian oil and gas sources3, turning to Azerbaijan instead. It is clear that Turkey’s strong interest, as well as ambiguousness and reluctance, in Azerbaijan comes from this relationship. Erdoğan has stated his support for Azerbaijan, but Azerbaijan’s relationship with Turkey is rather strained by opposing goals4. Supporting Azerbaijan is beneficial for their relationship, but a war in the region could threaten the access to oil and gas that Turkey spent so long trying to secure. For this reason Turkey is caught between two poles: it must maintain enough good-will with Armenia to make reconciliation with Azerbaijan possible in order to prevent a war, but at the same time it must stand with Azerbaijan in order to maintain the beneficial relationship and maintain energy security.

Knowing this, Armenia strengthens its relationship with Russia5, essentially securing itself a stronger position within the region. Turkey seeks independence from Russia by moving away from depending on its oil and gas; in response, Armenia invites Russia in and creates a threat to Turkey’s oil and gas while at the same time keeping Azerbaijan in a bind. In a sense, Armenia needs this conflict in order to hold power, or else risk being overran by Turkey to the left and Azerbaijan to the right. Leverage, in the form of endangering Turkey’s access to Azerbaijan’s oil and gas, is what makes Turkey and Russia come to Armenia for a deal. We must understand the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh as a clash between these interests, nations wielding their economic power in order to hold beneficial positions. This isn’t a mere conspiracy, rather access to resources and security is of existential importance to economies as we go through global recessions with increasing severity. Simply put, Nagorno-Karabakh is a crisis maintained by an increasing demand for profit— not merely an increasing demand by Azerbaijan, but of all foreign investors in Azerbaijan and the beneficiaries of its oil and gas exports as industries are battered in the economic contraction following COVID-19.

In 2019, I’d attended an address by the Minister of Defense for the Republic of Artsakh in Stepanakert. He showed us a map of the Golan Heights; he insisted that Israel’s occupation and de facto annexation of the Golan Heights set an international precedent that gave Armenia the international legal justification to hold Nagorno-Karabakh as its own territory. Surrounded by Armenians unlikely to find my views congenial, I left the room and lit up a cigarette outside on the street. I wondered how many of the Armenians on the street would have to pay for this territory in blood. I wondered how many of the other diaspora Armenians in the room accepted the Minister of Defense’s premises without skepticism or trepidation; how many accepted the lives of these Armenians on the streets of Stepanakert as a fair price?

What is Nagorno-Karabakh? Nominally, the reason for conflict is land and ethnic ties, but these claims can be made of many lands as Armenians have settled through much of that region that has exchanged hands and loyalties many times. It is Nagorno-Karabakh in particular that Armenia holds at tremendous expense, settling many people there in order to make it chiefly Armenian6, and pushing away the thousands of Azeris who are now refugees in their own country. In my time visiting Nagorno-Karabakh, I spoke with Armenian transplants who’d come from all over Armenia, paid to settle there and maintained by the government7 as besides the military there was no other work and population decline decimated the region. The implication is clear; the Armenian government is putting these people in harm’s way. It does so not in the interest of furthering the welfare of the Armenian peoples, or to preserve Armenian culture and traditions; it is a strategic move.

Again, I have no interest here in litigating who has the right to Nagorno-Karabakh. Rather I wish to point out that the Armenian people are paying an incredible price for Nagorno-Karabakh, both with the little money they have and the lives of their children. While every single Armenian proudly proclaims Nagorno-Karabakh to be Artsakh, many in private resent that so much of the little resources Armenia has goes to Artsakh. Much of what Armenians “make” comes from money sent by emigrants8. A man with whom I stayed in Nagorno-Karabakh told me that he understood little about the war even though he’d seen the rockets go into the air right from the balcony he stood in: “they die, we die. What difference does it make?” When I asked about the Armenian nation, he smiled with his gold teeth: “you have to die for your country. Can’t live for it.” In Stepanakert’s Museum of Fallen Soldiers, you see the tragedy of young men meant to fight other young men without ever being given the privilege of knowing what it was about. Many boasted of capturing the Azeri tanks and equipment left behind, but there’s a clear subtext: their Azeri enemies didn’t even see a purpose to fighting and easily relented. It’s no mystery why both sides in the Nagorno-Karabakh war hired mercenaries (Human Rights Watch/Helsinki 1994); the Chechen militant Shamil Basayev’s radio was proudly put on display in the museum.

If the Azeri men don’t see a reason to fight, why Nagorno-Karabakh? What is striking about the original conflict of 1988 is the temperamental indifference on the side of Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan has a superior force, with superior equipment and support from multiple nations, yet decisively lost and ceded territory to Armenia. And though Azerbaijan insists that Nagorno-Karabakh be returned them, it has shown little regard for the many refugees, of Armenian, Azeri, and many other ethnicities, that survived in poverty off of foreign aid (Human Rights Watch/Helsinki 1994). So what does the government of Azerbaijan see of value in Nagorno-Karabakh? I’ve already mentioned the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan and Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum oil and gas pipelines. I wish to stress that Azerbaijan’s chief concern here is economic security. The concern over these pipelines is not mine alone:

“A potential conflagration over Nagorno Karabakh is quite likely to affect both of these pipelines,” says Theodoras Tsakiris, assistant professor for energy, geopolitics, and economics at the University of Nicosia in Cyprus. “They are of critical significance primarily for Azerbaijan, then Turkey and, to a lesser extent, Europe and the global economy.” He notes that, in the case of a sustained conflict, Azerbaijan would likely shut down the pipelines for safety reasons to avoid oil spills and gas leaks if they were damaged. The most immediate impact upon Europe would be oil supplies. The pipeline link from Baku to Ceyhan, on Turkey’s eastern Mediterranean coast, carries some 1 billion barrels of oil per day, with most of it going to Europe plus some to Israel. Tsakiris notes that any cutoff would be a setback for the EU’s hopes of progressively reducing its current reliance on Russia for 35 percent of its crude oil supplies. (…) However, just as with oil, Brussels hopes one day to use Caspian gas to lower its current dependence on Russia for nearly one-third of its natural gas supply. Under its Southern Gas Corridor strategy, the EU hopes to see an additional 10 billion cubic meters of Caspian gas moving through new pipelines onward to southern and Central Europe by the early 2020s. That would be the first step toward even larger possible volumes in the future. “The important thing is to open up the corridor and have the possibility to build more pipelines through southeastern Europe which over the next 10 to 15 years could seriously open up the Caspian Sea generally for future supplies,” says Tsakiris. But so long as there is conflict in the Caucasus, any new pipeline projects remain risky financial propositions.9

Above all other historically Armenian lands, it is Nagorno-Karabakh that holds incredible leverage over the future of not only Azerbaijan’s economy, but also Turkey, Israel, and even the EU. Current clashes occurring in the Tovuz region hold considerable strategic import, as the Tovuz region is the site of the aforementioned pipelines10 and any pressure there could have disastrous consequences for an Azerbaijan completely dependent on oil and gas exports. Maintaining a hold over Nagorno-Karabakh allows Armenia to keep pressuring Azerbaijan, which at the same time also allows Russia to maintain its energy monopoly. For this reason, Russia has given military and economic support to both Armenia and Azerbaijan, selling weapons to both sides and then pressuring both sides for compromise and supporting Russian development initiatives11. Therefore, neither Armenia nor Russia can deter from holding Nagorno-Karabakh— without it, bargaining positions against Azerbaijan and Turkey would be significantly weaker. A continual crisis keeps this status-quo in position, the expense being the lives of Armenians and Azeri who are compelled to fight against their own interests. The narrative of ethnic tensions and who-owns-the-land hides this reality, reducing the complexity of geopolitics involving the policies of most of Europe down to a question of Armenian versus Azeri ethnicity. However, I argue this is not the case as all governments involved in the conflict have openly-stated economic and political ambitions— these ambitions are not unstable nor irrational, they follow clearly from the status-quo.

In the case of Armenia and Azerbaijan, questions of ethnicity and conflict here function as a false consciousness which obscures the economic basis that have created the current status-quo. The root of Armenia and Azerbaijan’s respective ethnic ideologies is a need to make current conditions universal and thus unchangeable, rather than dependent on the economic relationships that inform what is said and done in society. The interests of Armenia and Azerbaijan as governments is made synonymous with that of its peoples, so that the soldier who fights and dies at the front-line is falsely believed to share interests and motivations with the ruling class purely on the basis of sharing an ethnicity. However, this is clearly not the case— though it may be in the government of Azerbaijan’s best interest to sow conflict alongside ethnic lines and thus strengthen pan-Turkic nationalism, the resulting conflict and instability is felt as tragedy and hardship by the Azeris unfortunate enough to be swept into conflict. To understand the material conditions which have led to the current Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the idea that both the ruling class and the ordinary people involved share communal interests in the conflict should be questioned. By analyzing the material conditions and economic motivations of both Armenia and Azerbaijan, it is clear whatever Azerbaijan and Armenia as governments stand to win in this conflict must be weighed against what the ordinary people of Azerbaijan and Armenia stand to lose. More importantly, the ordinary people of Armenia and Azerbaijan must understand these material conditions— without overcoming the false consciousness I’ve spoken of here, every conflict becomes ideological and the basis of it becomes mysterious. Through ideology, conflicts are not understood to be rooted in economic or political matters but rather irrational, unchangeable impulses. Through ideology, Armenians and Azeris do not understand their conflict as that of conflicting global economic interests but a racialized fight to the death between two inherent enemies.

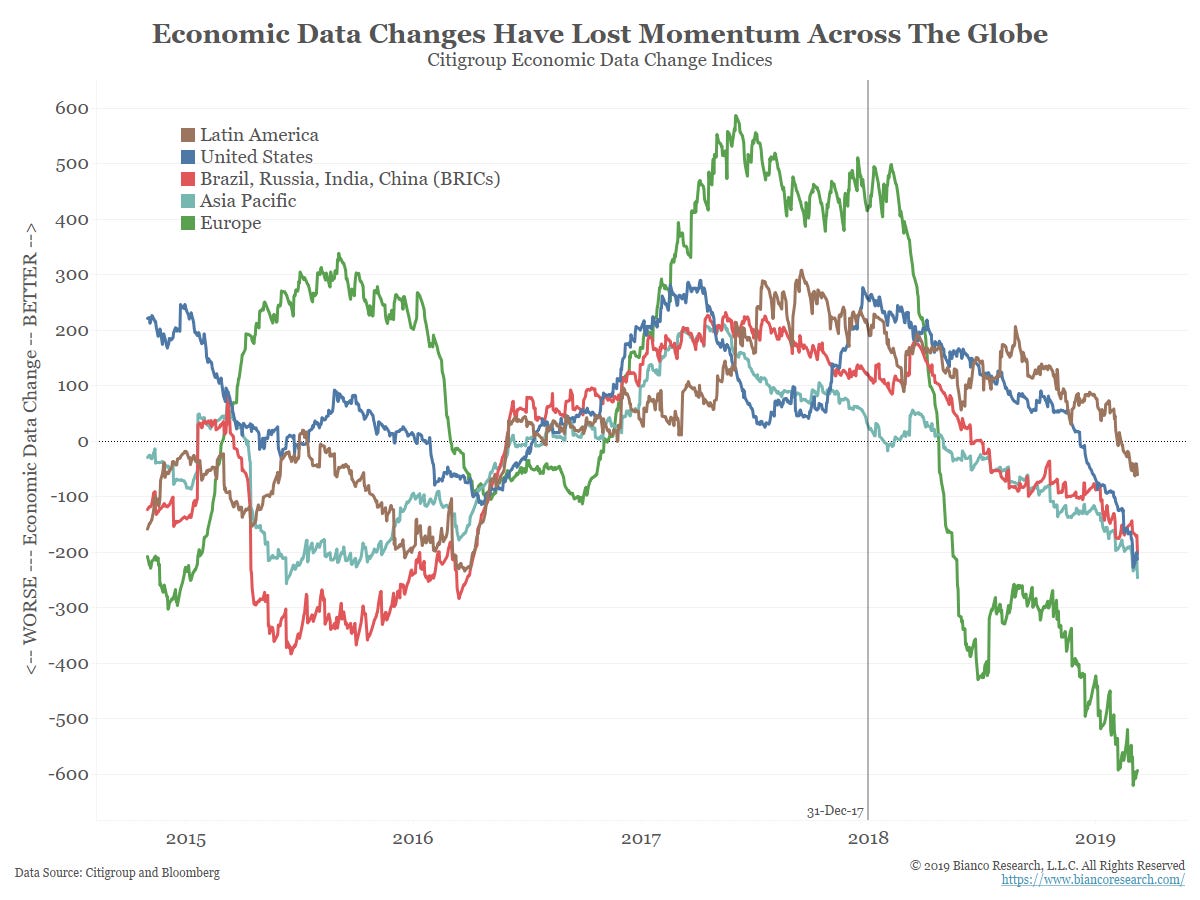

Lastly, I’d like to address these global economic interests. We understand that Azerbaijan’s pan-Turkic ambitions are part of the continuing collapse of the Soviet status-quo, beginning in 1991 when the collapse of the second largest economy and military alliance left a gigantic power vacuum in Europe and Asia. We understand that Azerbaijan’s growing oil and gas economy makes it a likely regional power in the near-future, making it of considerable interest to Turkey, Israel, and the EU who seek alternatives to Russia’s oil and gas. We understand that Armenia’s position in Nagorno-Karabakh allows it to wield considerable leverage over Azerbaijan and Turkey, two larger countries at its borders. We understand that Russia benefits from this conflict, as insecurities in Azerbaijan’s oil and gas economy make Russia’s own exports more attractive. But by what mechanism is it that global geopolitics can affect this rather small conflict?

To answer that question, we must first understand the vital distinctions between what is called the core and the periphery. To define them in simple terms, the core are the economic powers which are the beneficiaries of globalization, those with high profits and income. In contrast, the periphery are those states with low profits and income which support the core through cheap resources and labor. As states in the periphery to the core formed by economic powers such as the European Union, the states of the Caucasus function essentially as permanently under-developed zones in which labor and raw materials can be supplied at more competitive rates. This is the value of economic hegemony on a global scale— profit can remain within the site of consumption where it can be sold while the cost of production remains low. This division of labor is what makes globalization so successful, as not only do profits remain maximized but the material conditions of that labor remain obscure and therefore invisible to political life. Europe and the United States can enjoy the living standards of a post-industrialized nation while the nasty and violent work of resource extraction and commodity production happens in the mysterious zones peripheral to the core. This has two primary effects:

—firstly, resources and the labor necessary to produce commodities disappear from the imagination of those in the core. The average voter consumes these commodities but does not need to consider where the commodities come from as such matters exist outside of their society. As a concrete example: consider that the EU economy relied on 512.5 million tonnes of crude oil imports in 201812. The vast majority of these imports came from Russia, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia— far-away places to which the average EU voter has no connection to political processes or labor practices. Yet every time an EU voter consumes a commodity downstream from the crude oil industry, she is a beneficiary of an entire system of production that begins with its extraction from foreign soil. The entire process is inherently political, yet the EU voter can consider herself safely divorced from the corruption, exploitation, and instability that occur in oil and gas exporting states. Even the EU voter acutely aware of the production process has no political rights to exercise, as division of labor is also a division of political responsibility. Simply put, the EU enjoys cheap oil and gas without the negative side-effects of corruption, exploitation, and instability.

—secondly, what happens to the resources and labor necessary to produce commodities remains a complete mystery to those outside of the core. A worker in the petroleum industry of Azerbaijan does the labor necessary to produce crude oil and natural gas, but the fruits of that labor do not exist for that worker as neither the profit resulting from its sale nor the resources it produces remains in Azerbaijan. Rather the rich resources of Azerbaijan are extracted and sold by the Azerbaijan International Operating Company, consisting of mostly foreign corporate entities who take advantage of Azerbaijan’s low labor and land costs in order to maximize profitability when the commodity is later sold back to the core. Economic and political pressure force governments into contracts with these corporate entities, often resulting in political systems rife with corruption and authoritarian abuses as fulfilling contracts with foreign entities begins to take precedence over the well-being of citizens. Due to this, a citizen of Azerbaijan has a false understanding of the pressures and internal processes which govern the country as he has no political rights to exercise over the economic affairs of foreign entities nor any relationship to the profit nor resources that these affairs produce. Instability and even outward violent resistance against the government may occur, but they are inconsequential as the political life of an Azerbaijan citizen is completely removed from the economic affairs of foreign entities that operate within Azerbaijan. Corruption, exploitation, and instability become accepted as the norm— a price paid for joining global trade and thus stimulating economic development. Life in Azerbaijan is essentially restructured, and social relations conform to the demands placed upon Azerbaijan by its reliance on the production of gas and oil:

Social relations are closely bound up with productive forces. In acquiring new productive forces men change their mode of production; and in changing their mode of production, in changing the way of earning their living, they change all their social relations. The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist. The same men who establish their social relations in conformity with the material productivity, produce also principles, ideas, and categories, in conformity with their social relations. Thus the ideas, these categories, are as little eternal as the relations they express. They are historical and transitory products. (…) The production relations of every society form a whole. (Marx 1975)

These effects represent a modern form of imperialism, in which authority of global powers is extended over other states not by military or political domination, but rather by commodity production and trade. This division of labor and thus political responsibility is maintained by the wealth that results in the profits gained by selling the commodities. Even though Azerbaijan’s resources are its own, it is the partners of the Azerbaijan International Operating Company13 that reap its profit which in turn makes Azerbaijan dependent on its export partners for investment and economic development, as well as foreign military support and funding to protect investments14. This isn’t by plan or conspiracy, but rather the result of a system where resource extraction, commodity production, and profit accumulation are separated and made global:

It is characteristic of capitalism in general that the ownership of capital is separated from the application of capital to production, that money capital is separated from industrial or productive capital, and that the rentier who lives entirely on income obtained from money capital, is separated from the entrepreneur and from all who are directly concerned in the management of capital. Imperialism, or the domination of finance capital, is that highest stage of capitalism in which this separation reaches vast proportions. The supremacy of finance capital over all other forms of capital means the predominance of the rentier and of the financial oligarchy; it means that a small number of financially “powerful” states stand out among all the rest. The extent to which this process is going on may be judged from the statistics on emissions, i.e., the issue of all kinds of securities. (Lenin 1939)

It is for this reason that we cannot call Nagorno-Karabakh merely a regional dispute, but must understand it as an imperialistic conflict. Armenia and Azerbaijan did not create the current status-quo of global capitalism, they merely respond to it. Though it is the ordinary Armenian and Azeri that is asked to work and die for their country, it can be shown merely through the economic realities of both countries that the ruling class and foreign investors are those with stakes in this conflict. Though ideology and common sentiment give the impression that the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is a inevitable expression of ethnic tension, an understanding of political and economic motivations reveals that global pressure on Azerbaijan to deliver cheap exports of oil and gas is forcing this confrontation to extremes that make as little sense to the outsider as they do to those involved. It is only by rejecting this false consciousness, rejecting the notion of an inevitable struggle between Armenians and Azeris, that we can bring these pressures to light and understand that whatever there is to win in the Nagorno-Karabakh war, ordinary Armenians and Azeris can only lose.

In 2020 before I’d left Armenia, I’d found myself in Meghri ‘round the Iranian border. It was autumn, and the trees has begun to shed their leaves. People were collecting what they’d grown along the roads. I was traveling along with a few French healthcare volunteers, and we stayed with a single mother and a young boy in a large but decaying house up on a hill. Their main business was dried fruits, and they’d let us sample their apricots and pomegranates all night. In their living room, the mother showed me the French suitor she’d nabbed on Facebook, sitting beside a row of pictures. One of the pictures had an older man who looked so similar to the young boy. I asked the young boy where his father was, and the young boy said, in that most Armenian manner: “he was done. It happened in war.” In the other pictures, the young boy looked proud with a soccer ball in his arms. I asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up, and he said Messi or Ronaldo. He showed me the posters he had in his room. I translated my French companions’ words of encouragement. After a while, the young boy asked me if I knew any interesting songs. I went to their aging piano, and played a song in French:

Fils de bourgeois / ou fils d`apôtres

Tous les enfants / sont comme les vôtres

Fils de César / ou fils de rien

Tous les enfants / sont comme le tien

Le même sourire / les mêmes larmes

Les mêmes alarmes / les mêmes soupirs

Fils de César / ou fils de rien

Tous les enfants / sont comme le tien

Touraj Atabaki, “Recasting Oneself, Rejecting the Other: Pan-Turkism and Iranian Nationalism” in Van Schendel, Willem(Editor). Identity Politics in Central Asia and the Muslim World: Nationalism, Ethnicity and Labour in the Twentieth Century. London, GBR: I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited, 2001.

Raoul Motika, « Islam in Post-Soviet Azerbaijan », Archives de sciences sociales des religions, 115 | 2001, 111-124.

Ilham Aliyev, https://web.archive.org/web/20140622193215/http://en.president.az/articles/4423. 2012.

Marx, K. (1975). The poverty of philosophy: Answer to the “Philosophy of Poverty” by M. Proudhon. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich. Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism: A Popular Outline. New York: International Publishers, 1939.

Human Rights Watch/Helsinki (Organization : U.S.), Panico, C., Rone, J., & Human Rights Watch (Organization). (1994). Azerbaijan: Seven years of conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. New York: Human Rights Watch.